U-550 & SS Pan Pennsylvania

The Hunt for the Last U-boat

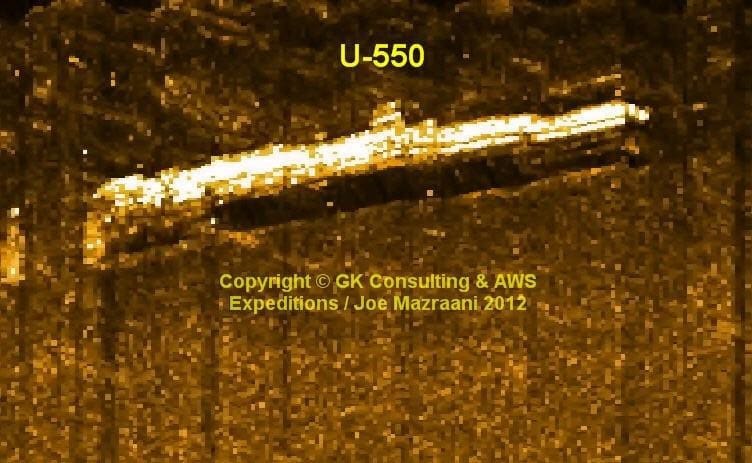

It should go without saying that finding U-550, the last U-boat resting in diveable Northeast Atlantic waters, was a major moment in the lives of the D/V Tenacious discovery team. As is often the case however, the discovery was only the beginning of a larger and more meaningful story. D/V Tenacious and a crew of seasoned divers and technicians discovered U-550 and the stern of the Pan Pennsylvania (“Pan Penn”) in the summer of 2012. Some of the team members had been searching for the elusive German submarine for more than twenty years. What they could not have anticipated was that the discovery of U-550 would connect people across time and across continents. It would bring together American sailors, then in their nineties, who had survived the battle between U-550 and its target, Pan Penn. It would connect German sailors still attempting to make peace with a war that they fought not necessarily out of conviction but out of duty. Finally, the discovery of U-550 would enable the team to dispel two myths, one that had long persisted about the sinking of Pan Penn and the other about the fate of forty-two German soldiers who had been all but erased from official accounts of the battle.

The Battle

It was 1944. WWII’s Battle of the Atlantic raged. German U-boats roamed America’s Eastern coast hunting for merchant and military ships carrying goods, supplies and soldiers to our allies in Europe. On April 16, 1944, the German submarine U-550, a type IXC/40 long-range U-boat under the command of Captain Klaus Hanert, put a single torpedo just forward of the stern engine space of the 10,017-ton American tanker Pan Pennsylvania. Pan Penn was, at the time, the largest tanker in the world and traveling in a convoy bound for England loaded with 140,000 barrels of gasoline. Following the torpedo explosion, the ship took on an immediate list to port and quickly caught on fire. The tanker was abandoned in short order. The convoy escorts picked up 56 survivors, leaving 25 men missing out of a crew of 81. Those men died when they prematurely attempted to board lifeboats and either succumbed to toxic fumes or fell into waters of burning gasoline.

After picking up the survivors from Pan Penn, the U.S. Navy destroyer escorts USS Joyce, USS Peterson and USS Gandy combined their efforts to bring swift and fatal retribution to the attacking submarine. Picking up a solid contact with her sonar gear, Joyce closed on the target and made a depth-charge attack that quickly brought U-550 to the surface. During the battle, Gandy rammed the submarine abaft the conning tower.

German sailors poured out of U-550’s hatches and abandoned ship.

U-550 crew gathering on deck.

Chief Engineer Hugo Renzmann opened flooded the boat in order to sink U- 550 before she fell into enemy hands. U-550 sank stern first. Twelve survivors from the submarine were picked up by the destroyer escorts, while 42 Germans were reported as lost.

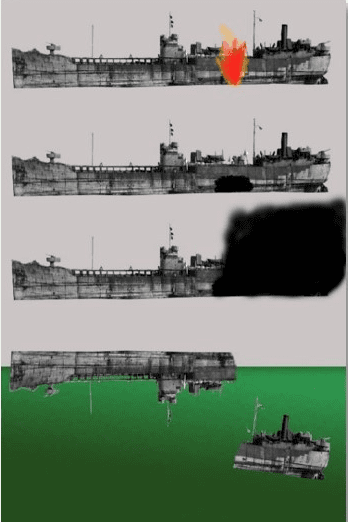

The tanker Pan Penn capsized and drifted for two days, her cargo of gasoline on fire, before finally being sunk with gunfire. Those who were there and historians who studied the photographs afterwards believed that Pan Penn's stern remained intact and that she sank whole.

SS Pan Penn burning, her stern obscured by smoke.

The People

The discovery of U-550 made international news and soon several people, some extremely unexpected, reached out to Mazraani with information and inquiries.

Among them:

- Mort Raphelson, Chief Radio Operator on the Pan Penn

- Richard Hudock, sailor on the Gandy

- Wolf Hanert, son of U-550’s captain

- John Rauh, son of U-550’s machinist mate

The crew spent the next few years interviewing these men and putting together the remaining pieces of what occurred on April 16, 1944.

Mazraani learned that three of U-550’s crew were still alive in Germany and reached out to Hugo Renzmann, Chief Engineer of U-550, Albert Nitsche, Steward and Gunner on U-550 and Robert Ziemer, Sailor on U-550.

The team traveled to Germany to interview them. Two of three, Albert Nitsche and Hugo Renzmann agreed to interviews, which were videotaped. Despite the crew’s attempts, Robert Ziemer, the third veteran, refused to talk about his experiences in WWII, but Mazraani and Author Randall Peffer did have one significant telephone conversation with him during which Ziemer explained that he did not want to relive those memories.

Joe Mazraani with Wolf Hanert and Renzmann in Germany.

Johan and John Rauh

Johan Rauh, the machinist’s mate on board U-550, served two years in the United States as prisoner of war. After the war, he returned to Germany for a short time but later moved to the United States and settled in Long Island. In the summer of 2017, his son, John Rauh, joined the crew on a visit to U-550’s resting place.

John Rauh (second from right) with divers on the 2017 expedition. Photo © Jennifer Sellitti 2017.

Five German sailors aboard Joyce. John Rauh’s father, U-550 machinist Johan Rauh is second from right.

Solving Mysteries

During the anti-submarine engagement, Pan Penn was set on fire by stray fire from the destroyer escorts. The tanker turned upside down and floated as a derelict for two days until sunk on April 18 by U.S. Navy aircraft and shellfire. The wreck of Pan Penn, then thought to be whole, was first dived in 1994 and was found lying partially upside down on the ocean bottom at 73 meters (240 feet).

The discovery of U-550 revealed that this was not the case. The team undertook two side-scan sonar expeditions to search for the German submarine in 2011 and 2012. In addition to finding U-550, one of the search trips yielded an unknown large contact, which was subsequently dived as part of a 2013 expedition and determined to be Pan Penn's stern. The stern section lies on its port side in far deeper water, and is separated from the wreck site of the bow section by a considerable distance. It had broken off during the fire but because it was obscured by smoke, no one saw it happen.

A diagram of how Pan Penn's stern broke off and sank.

The Fate of 42 German Sailors

Another and far more sobering mystery was solved through interviews with crewmembers from both ships. Official reports indicated that the Germans fired on the American with their weapons when they surfaced before swimming to the destroyer escorts. Strangely, none of the sailors interviewed by Mazraani recalled this. The U-boat had a crew of 54 men. Twelve were picked up by Joyce. None of the reports explained exactly what happened to the other 42. The inference was that they somehow died in the battle or on the swim. Neither made much sense given the circumstances of the sinking or the proximity of U-550 to the destroyers.

This mystery was solved by two men – American sailor, Collingswood Harris, who served aboard the Peterson and Robert Zeimer. In the aftermath of the U-550 discovery, Mazraani had communicated with the three living German sailors, including Zeimer. He called him to see if he could shed light on what happened to the missing crew. Zeimer paused before telling a disturbing tale. Captain Hanert had gathered the men on the foredeck and told them to swim to the closest destroyer escort. The men donned life vests and escape lungs. Zeimer, the captain, and 10 others would wait until the second wave to leave the U-boat. Zeimer watched as more than forty of his fellow sailors swam towards Peterson only to see the ship back away from them and leaving them to float away. He and the other survivors swam to the Joyce. It was so painful to go back to the moment in which he watched his brothers die in the water that he refused to conduct an interview with the discovery team when they told him that they were coming to Germany to interview Nitsche and Renzmann. “Horror” was what he called it.

In 1984, Collingswood Harris conducted an interview with a historian from the Coast Guard about his time aboard the Peterson and the sinking of U-550. The crew unearthed the interview after speaking to Zeimer. Harris described what he called the “euphoria” of the men on his ship. Euphoria turned into wanton firing in the water at German soldiers. What Harris and Zeimer’s stories revealed is that no living Germans had gone down with the ship. More than forty men died because the men aboard the Peterson shot at German sailors attempting to surrender and left the remaining men to float away and die in the frigid water. This explains how three dead German sailors, wearing life vests and escape lungs, turned up adrift in the North Atlantic weeks after the battle.

U-550 on the surface with sailors swimming towards one of the destroyer escorts.

Photos by Brad Sheard

Diver/Photographer Brad Sheard has chronicled the crew’s first dives on U-550 and Pan Penn. His stunning images can be found here: http://bradsheard.com/u550.html.

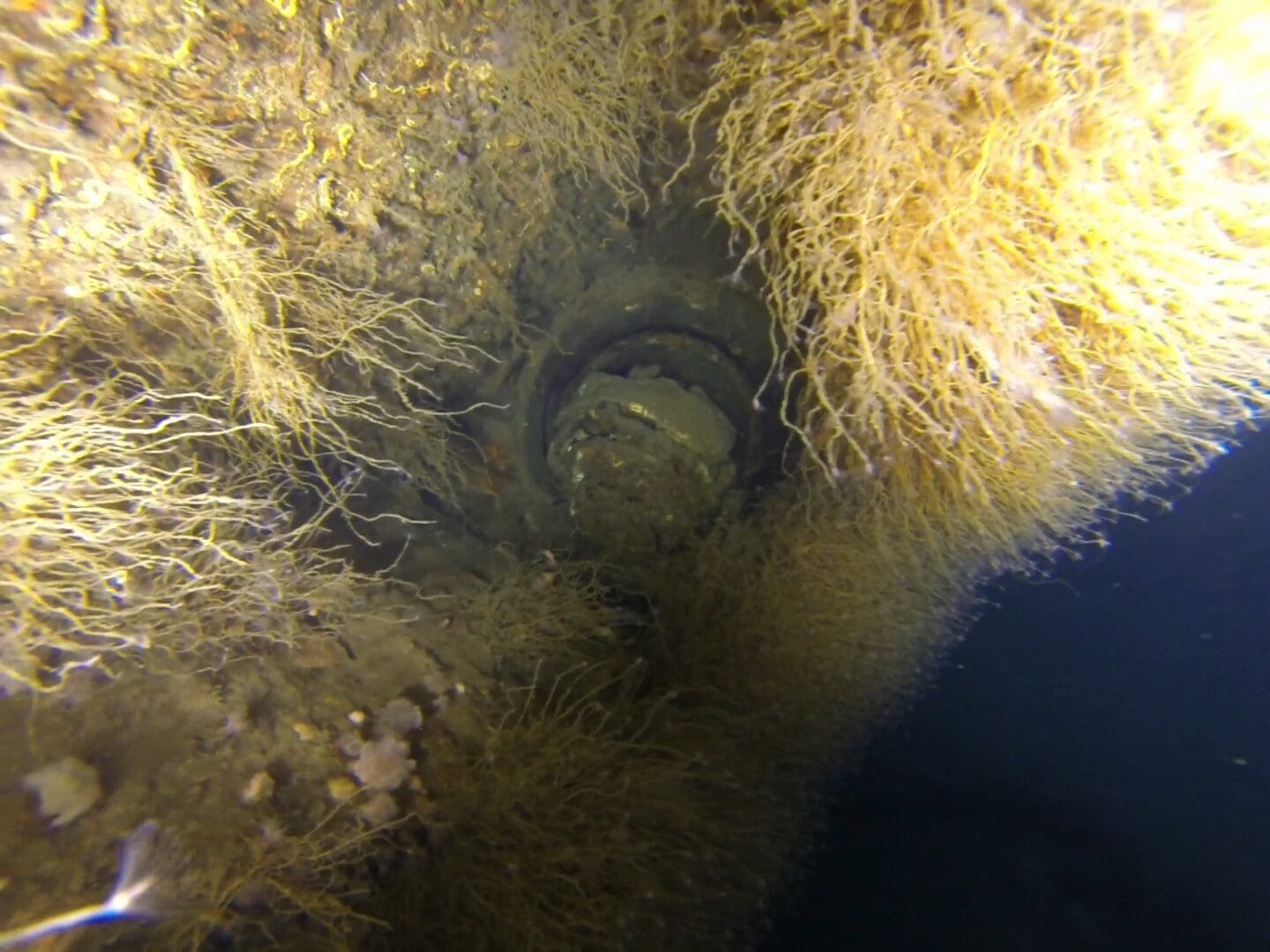

The following images provide an idea of what the ships currently look like at the bottom of the ocean. They are remarkably well preserved. U-550’s outer hull remains intact, making her an extraordinarily well-preserved example of a WWII German U-boat.

Diver Mark Nix at U-550’s knife-edge bow.

Divers explore U-550’s conning tower.

Joe Mazraani swims towards Pan Penn’s propeller.

Dcoumenting the Wrecks

Additional photo and video documentation has been gathered by the team in the twelve years since the wrecks were discovered.

A torpedo ready to fire from U-550's forward torpedo hatch. Photo © Joe Mazraani 2012.

Where Divers Dare

The full story of the discovery and what happened in the years that followed can be found in the book "Where Divers Dare, the Hunt for the Last U-Boat." The book explores wreck diving in the North Atlantic, the competition for discovery of U-550, the crew’s connection to survivors, the trip to Germany in search of German sailors from U-550, and personal stories of Americans and Germans who survived the battle. The book is available at online booksellers and dive shops worldwide

2020 Expedition

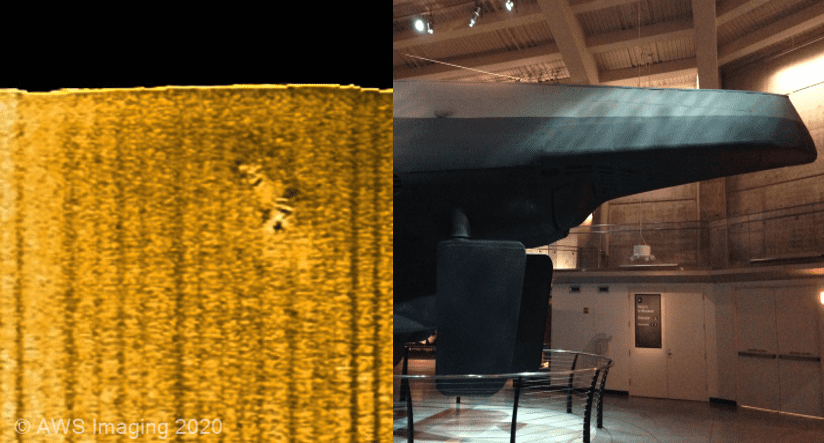

Atlantic Wreck Salvage has mounted several expeditions to U-550 and Pan Penn since 2012. The goal of the 2020 Expedition was to obtain new sonar images of both shipwrecks and to dive the wrecks to determine their current condition. In addition to obtaining up-to-date sonar images, the 2020 Expedition Team made another noteworthy discovery when it located U-550’s “tail bustle” resting approximately 200 meters from the U-550 wreck site. Shortly after the submarine was depth charged, destroyer escort USS Gandy claimed to have rammed U-550 amidship as the submarine struggled on the surface. There was some speculation the ramming might have damaged the submarine’s pressure hull and contributed to her sinking. During an interview with surviving U-550 crew member Hugo Renzmann, he claimed U-550 had not been rammed and that the interior of the submarine had not been breached until the crew themselves opened a sea strainer and flooded the vessel.

Diver Harold Moyers, part of the 2012 expedition/discovery team, noticed the tail bustle was missing on one of his early dives to the wreck, leading him to believe the ramming caused only superficial damage to U-550. Moyers observed the stern was sheared off cleanly just behind the pressure hull. The discovery of the tail proved the Gandy rammed U-550 but farther aft than claimed. It also confirms it did not cause her to sink.

Side scan sonar image of the tail bustle compared to the U-505 tail bustle. Photo of U-505 tail bustle © Joe Mazraani.