SS Carolina Project

U-151’s June 2, 1918 Attack Off the New Jersey Coast

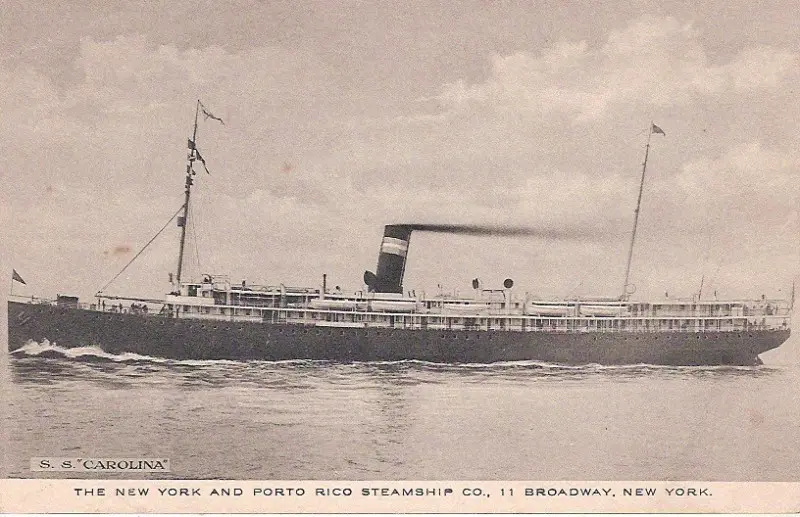

SS Carolina was built in 1896 by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company. She was 380 feet long and a little more than 5,000 gross tons. She was christened as La Grande Duchesse, and following her sea trials, delivered to The Plant Investment Company. Plant initially refused delivery because of boiler and propeller problems but accepted her after a refit. In 1906, a short stint steaming for Ocean Steamship Company as The City of Savannah, New York and Porto Rico Steamship Company purchased her and renamed her SS Carolina. She spent much of her life plagued with mechanical problems, including vibrations from her twin-screw configuration that caused some difficulty maneuvering. Newport News refit her again in 1913 and reduced her to a single screw, which significantly improved the ship’s performance.

Many Puerto Ricans came to New York aboard Carolina from 1906-1918 in search of opportunity. Jesus Colon was one of them. A Brooklyn Puerto Rican activist, he traveled to New York on the Carolina in 1917. At 16 years old, he convinced his friends who worked on the crew to hide him in the linen closet to escape to New York without paying for a ticket. His friends snuck him onto the boat, but a crew member quickly found out and reported him. The Captain put him to work polishing the fine China in exchange for his fare. “I still remember the name of the boat – SS Carolina, an old ship painted in funeral black around the hull and in hospital white from the deck up.” he later recalled. In the decades after Carolina’s sinking, travelers and survivors fondly remembered the ship at gatherings in both New York and Puerto Rico. Years later, the band leader Rafael Cortijo with singer Ismael Rivera recorded “Carolina,” a lively song that celebrates the ship.

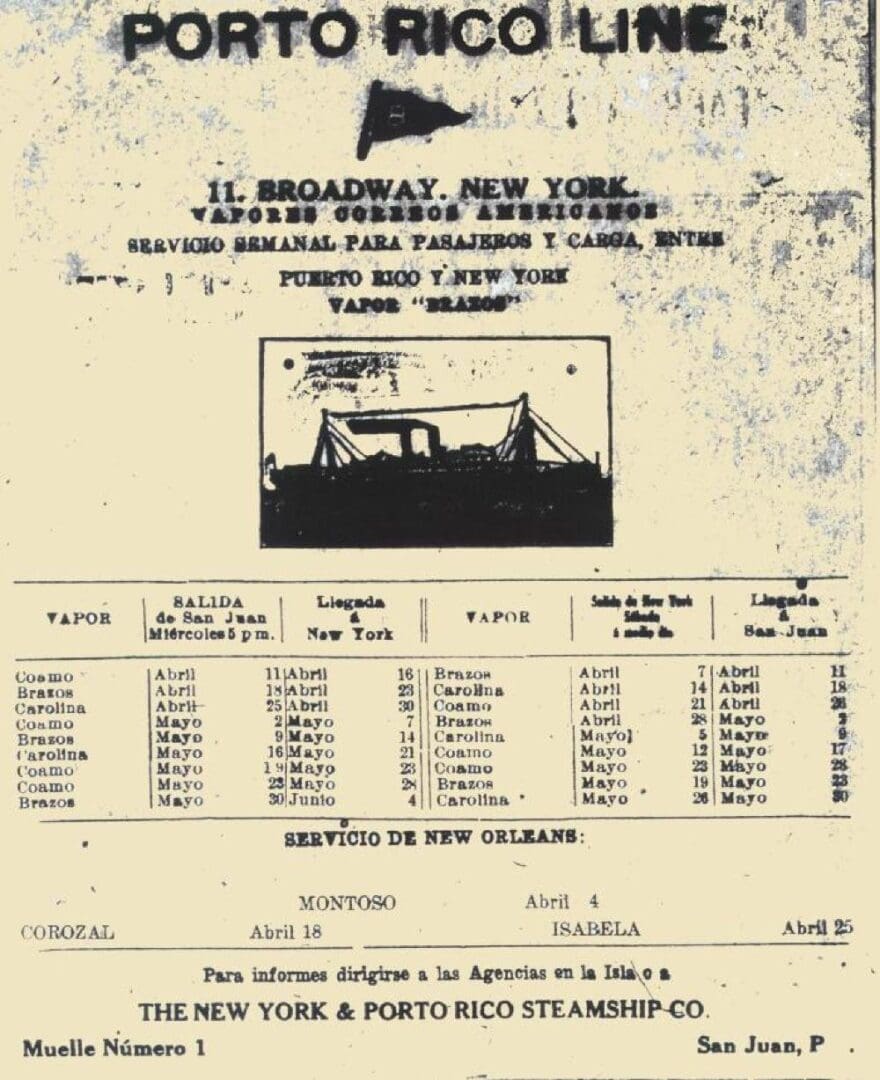

Spanish-language advertisement for the Porto Rico Line, including voyages on SS Carolina.

Colon made it safely to New York on his 1917 voyage, but passengers on the May 1918 voyage from Puerto Rico to New York were not as lucky. SS Carolina left San Juan on May 29, 1918, with 218 passengers, 117 crew members, and a cargo of sugar. On Sunday, June 2, she received a radio S.O.S. from the American schooner, Isabel B Wiley. The Wiley reported being under attack by a submarine. Carolina’s master, Captain Barber, ordered full speed and steered away from the reported location but could not escape the submarine. U-151 fired three warning shots from her deck guns and signaled for Carolina’s passengers and crew to abandon ship. Captain Barber launched the ship’s lifeboats. Women and children embarked first, and the boats began to launch at 6:30 p.m.

Captain Barber was the last to leave the ship. He later explained, “After I had seen everyone off the ship into the boats, and after I had destroyed all the secret and confidential papers, I, myself, got into the chief officer’s boat, this being the only boat left alongside.” Once the ship had been evacuated, U-151 fired three further shells into the ship’s port side. She sank a little more than an hour later, at 7:55.

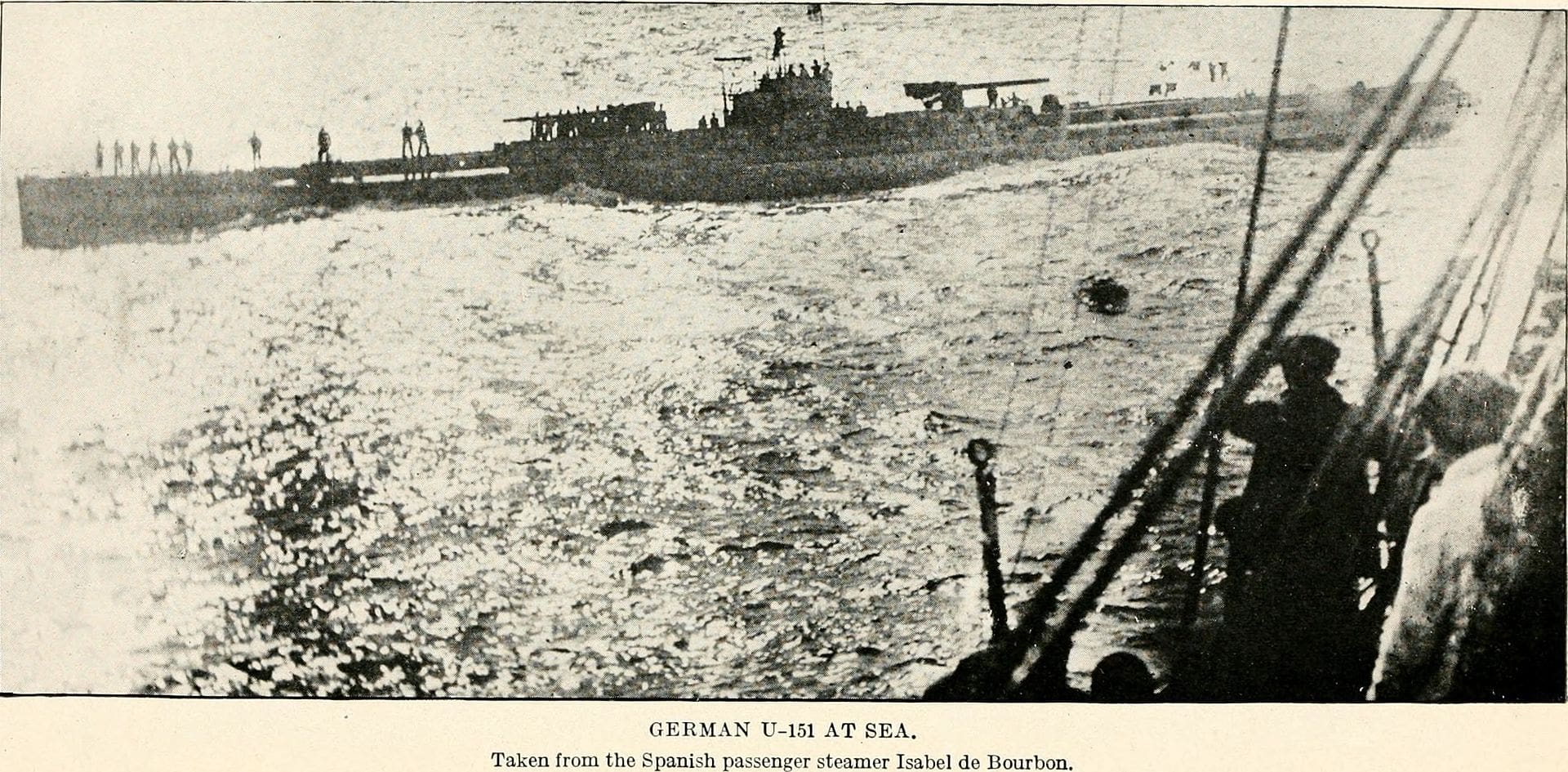

Carolina was just one of the vessels U-151 claimed that day. In all, she sank six ships and damaged two more over the course of about two hours. These included the liner SS Carolina, the freighters Winneconne and Texel, the schooner Isabel B. Wiley, and two other schooners, all with a combined crew and passengers of about 448 people. In all cases, U-151 fired warning shots and gave the crews time to abandon ship in an orderly fashion—women and children first in the case of Carolina—before sinking them with gunfire. The success of the attack prompted some to refer to the events of June 2, 1918 collectively as “Black Sunday.”

A photograph of U-151 taken from a passenger steamer.

Carolina’s fate was unknown on the evening of June 2, and newspapers speculated the worst. The night was stormy, and the ship’s boats tried to stay together. The submarine had attacked at supper time. Many of Carolina’s women passengers were dressed in their evening gowns when they took to the boats. The passengers and crew suffered greatly from exposure during the storm.

One lifeboat made it to Atlantic City and others were picked up by passing ships. New Jersey residents welcomed survivors with open arms and hotel operators opened their establishments to them. Thirteen died (eight male passengers and five crewmen out of 218 passengers and 117 crew), when one of Carolina’s lifeboats capsized. The Danish steamship Bryssel found their swamped motorboat. It was the first loss of life caused by U-boat activity off the United States’ Atlantic seaboard.

No one knew the offending submarine’s identity at the time. Samuel Johnson, one of Carolina’s survivors, did his best to describe the U-boat, “[It] was painted green, almost the color of the ocean. It vanished in no time after she made sure the Carolina would sink.” He added, “She was the biggest submarine I ever saw, and I’ve seen a lot of them. She must have been a super submarine because she was at least 250 feet long.” Daily New Era, June 5, 1918. He was almost correct. U-151 was 213 feet long and among the largest class of U-boats of WWI. U-151 was originally one of seven Deutschland class “merchant” U-boats designed to carry cargo between the United States and Germany in 1916. Five of the submarine freighters were converted into long-range cruiser U-boats and equipped with arms. Armed with two 5.9-inch deck guns, two 20-inch torpedo tubes, 18 torpedoes, as well as mines, these were the largest (1,500 tons and a crew of six officers and 50 men), most heavily armed submarines in the world, and possessed enough range to reach the United States Eastern Seaboard and operate there for over a month.

U-151 was constructed by Reiherstieg Schiffswerfte & Maschinenfabrik at Hamburg and launched on 4 April 1917. From 21 July to 26 December 1917 she was commanded by Waldemar Kophamel who took U-151 on a long-range cruise which eventually covered a total of 12,000 miles.

U-151 departed Kiel, Germany, on April 14, 1918 bound for the United States. This was the first time a German submarine sailed to the western Atlantic intent on attacking shipping. She was under the command of Korvettenkapitän Heinrich von Nostitz und Jänckendorff. Her voyage was no secret to the Allies due to the broken codes, but this fact was successfully kept from the Germans. After laying mines, cutting cable, and sinking three fishing schooners, U-151 finally made her presence known on June 2. The attack took the Americans by surprise despite their knowledge that U-151 was operating off the Eastern Seaboard.

The following day, on June 3, the tanker Herbert L. Pratt struck one of the mines laid by U-151 off the Delaware Capes and sank. The ship was later raised. U-151 stopped the Norwegian cargo ship Vindeggan off Cape Hatteras on June 9 and set scuttling charges after transferring 70 tons of copper ingots off the vessel. U-151 engaged in other attacks off the Eastern Seaboard and returned to Kiel on 20 July 1918 after a 94-day cruise in which she had covered a distance of 10,915 nautical miles (20,215 km; 12,561 mi). She claimed 27 ships in all, 23 by direct attack and four by her minefields.

The wreck was first dived by John Chatterton, John Yurga, Brad Sheard and Barb Lander. Chatterton lodged a salvage claim in the New Jersey Federal district court, arresting the ship. After recovering the purser’s safe in 2000, he abandoned his claim to the wreck.

Atlantic Wreck Salvage, LLC and the Arrest of SS Carolina

SS Carolina's engine.

Atlantic Wreck Salvage, LLC arrested the abandoned wreck of SS Carolina in 2014. The U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey, Honorable Joseph H. Rodriguez, ultimately granted AWS exclusive and sole salvage rights to the vessel in the matter of Atlantic Wreck Salvage, L.L.C. v. The Wrecked and Abandoned Vessel known as SS CAROLINA, which sank in 1918, her engines, tackle, appurtenances and cargo, No. 1:14-cv-03280-JHR-KMW.

The concept that a wreck can be “owned” by a salvor yet still enjoyed by the wreck community is not new. Simon Mills owns title to the HMHS Britannic. The late Greg Bemis owned title to RMS Lusitania. John Moyer, Steve Gatto, and Tom Packer own rights to SS Andrea Doria.

Offshore deep salvage requires an enormous commitment of both time and money. A salvor has no protection for his projects from opportunistic interlopers who may lie in wait until the object(s) being salvaged are already exposed and ready to be lifted to the surface and hoisted onto a waiting vessel.

Artifacts from SS Carolina are buried under heavy wreckage. Their recovery is part of AWS' ongoing salvage and historical preservation of the vessel.

Joe Mazraani has been diving the wreck since the late 1990s. Tom Packer and Joe searched for the remnants of the bridge and other items of interest such as the ship’s bell, its whistle, the engine room telegraph, gauge panel, and bow letters. In 2013, they found the bridge and decided to perfect an Admiralty arrest given the level of work required to free what they could see and access what is buried beneath wreckage and sand.

The concept of arresting a shipwreck does not sit well with some. AWS decided to arrest SS Carolina to protect the wreck and the efforts of our team. We have spent a lot of money and time recovering and restoring priceless artifacts lifted from her that the sea would have otherwise destroyed. These projects are not one-time visits to the wreck. They are ongoing and accomplished one small piece at a time. The only way to protect the time and effort our team has and continues to put into this salvage was to arrest the wreck.

AWS has no desire stop other divers from experiencing SS Carolina. Quite the contrary. She is magnificent, and we encourage those who are qualified to make the dive to visit her. AWS, however, now requires prior notice by divers and consent by AWS of any diving activity on the wrecked vessel. If you have an interest in diving SS Carolina or for more information about AWS’ ongoing salvage claim, please contact us.

AWS statement on SS Carolina

Download PDF

The above is not meant to be a complete description of AWS’ salvage interest in SS Carolina.

SS Carolina Telegraphs

AWS has recovered large portions of four of the Carolina’s telegraphs in an ongoing effort to restore them in full. They are by no means complete and AWS hopes more pieces of the telegraphs will be recovered in the coming years. The telegraphs are just some of the items being salvaged and restored from the vessel.

Four of Carolina’s telegraphs shortly after recovery and before restoration. Photo © D/V Tenacious.

The restoration is being done by Scott Ciardi of Brass from the Past in Dartmouth, Massachusetts. Scott is a master craftsman with decades of experience restoring brass artifacts and antiques.

Scott Ciardi of Brass from the Past (left) with D/V Tenacious Captain Joe Mazraani. Photo © Jennifer Sellitti 2021.

Similar telegraphs side-by-side before and after extensive restoration. Photo © Jennifer Sellitti 2021.

AWS has partnered with Sayreville Historical Society to display the restored telegraphs and other Carolina artifacts at a May 25, 2023 event that honored the ship and her strong connection to Puerto Rican history. The exhibit enabled members of the public to learn more about Carolina and U-151’s other victims and to view her telegraphs and other beautiful artifacts up close and personal. The event was a fundraiser for Sayreville Historical Society and all proceeds went to their mission of preserving and making accessible to the public the history of Sayreville, NJ and the surrounding region.

AWS and Sayreville Historical Society members at the SS Carolina event. Photo © D/V Tenacious 2023.