HMHS Britannic's Lost Bell

It should surprise no one that divers Joe Mazraani and Richard Simon grew up captivated by the adventures of Jacques Cousteau. Cousteau has inspired so many explorers that citing him as inspiration is somewhat cliché, but his connection to HMHS Britannic and, more specifically, to the May 2019 Expedition to the legendary shipwreck make the reference both relevant and necessary. Joe and Rick spent many an evening mesmerized by documentaries about the discoveries Cousteau made aboard his research vessel, Calypso. It was in December of 1975 that Cousteau and Dr. Harold Edgerton discovered the wreck of Britannic, one of the largest liners of her day and sister to an even more famous ship, Titanic. The documentary The Cousteau Odyssey: Calypso’s Search for the Britannic first appeared on television in November of 1977, before either Joe or Rick were born. A decade later, Rick and Joe watched the program in re-runs and each imagined making their own journeys to the Aegean Sea. Becoming part of the May 2019 Britannic Expedition was itself a dream fulfilled. What they did not know as young men or even as the seasoned technical divers who arrived in Athens in May of 2019 was that on their last dive together they would solve a mystery that long-surrounded Cousteau and contribute yet another piece to the unfolding historical record of Britannic.

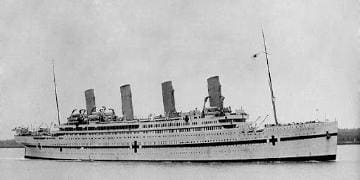

HMHS Britannic was among the largest ships of her day. She was the third vessel in White Star Line’s Olympic class, a class that included Olympic and Titanic. Unlike Titanic, Britannic never realized her potential for luxury because she was requisitioned by the British Royal Navy as a WWI hospital ship shortly after her launch and refitted for that purpose. Her Naval service lasted only a little less than a year. On November 21, 1916, Britannic was carrying almost 1,100 crew and hospital personnel when she struck a mine laid by a German U-boat.

Today, Britannic is one the world’s most sought-after wreck dives. She is a 100-foot-tall and 900-foot-long behemoth that rests on her starboard side at the bottom of the Kea Channel, a body of water between the islands of Kea and Makronissos, Greece. Since Cousteau’s first series of dives to the wreck in 1976, fewer than 100 divers have reached her. This is not only because access to the wreck is preciously guarded by the Greek government but because only the most experienced divers can reach her 400-foot depth.

In 2018, Joe met British Diver and Photographer Rick Ayrton on a dive trip to Truk Lagoon. Aytron told him that British wreck diver Scott Roberts was organizing an expedition to Britannic. Months later, when Roberts invited Joe and a dive buddy to join them, he and his longtime friend Rick Simon jumped at the chance. Other members of the team included: British divers Luke Kierman, Jacob MacKenzie, George McClure, Duncan McCormick, and Steve Pryor, and Australian diver Scott Wyatt.

The divers met in Athens, some for the first time. They sailed from mainland Greece to Kea Island on the tenth of May. Kea, known as a summertime playground for Greeks but not as often visited by foreign travelers, serves as home base for most modern Britannic expeditions both because of its proximity to the wreck and to Kea Divers, the only nearby dive shop with the expertise, equipment and staff to support technical divers.

The team heads out for its first dive on Britannic.

The excitement on the ferry ride from mainland Greece to Kea was palpable. It only increased when George Vandoros, the team’s surface support leader, greeted the team. George is a tall, rugged, full-bearded man from the Greek Island of Kefalonia with an engaging smile, boundless energy, and a penchant for chain-smoking hand-rolled cigarettes. One look at George inspires confidence. His credentials as a technical diver renown throughout Europe only solidify the impression. He would be responsible for making sure every diver returned safely from the depths.

George at first listened more than he spoke and silently assessed the knowledge and experience of each team member. When he was unsure about something, he squinted and cocked his head. When something pleased him, he sported a huge grin and nodded. Such telltale windows into his thoughts that would later come in handy for surface support crew who learned to react quickly to George when he needed something. George must have liked what he heard from the group because it did not take long for the team to gel. Soon the team of eleven huddled around a small plastic table built for only two drinking espresso and talking excitedly about dive plans, timetables, and gas mixes against the hazy backdrop of George’s cigarette smoke.

The ferry ride to Kea passed in a flash. The team touched land and got their first look at the island they would call home for the next two weeks. Restaurants and shops and grocery stores dotted the port. The colors from small villages nestled in the mountains shone in the sunlight. The team resisted any temptation to explore the island and went straight to work. Although the island was new to them the object of their journey, Britannic, was not, and she occupied their thoughts.

Britannic was one of the largest passenger ships in the world when she launched on February 26, 1914. 50,000 tons. Almost 900 feet long. 175 feet to the top of her funnels. A carrying capacity of more than 3,300 passengers and crew. A speed of 21 knots. Shipbuilders Harland and Wolff of Belfast had laid Britannic’s keel in 1911, but the disaster that befell Titanic caused them to make several design modifications and delay her launch. These included structural improvements, an expansion of the number and height of her bulkheads, additional lifeboats, and improvements to lifeboat davits and launch capabilities.

Britannic was built to be as opulent and luxurious as her sister with the added bonuses of being larger and safer. Her halls, staircases, and ceilings were designed to be as beautiful as those that drew the wealthiest passengers to Titanic. Her bow was identical to the one made famous by Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet in James Cameron’s fictional account of Titanic’s voyage. Her decks were as broad and grand as her sister’s. She was, in most important ways, Titanic’s twin but would never know the feeling of exclusive, transatlantic passenger travel. The British Royal Navy drafted her after her launch but before she set sail on a single commercial voyage. Britannic would find purpose not in entertaining the most discerning aristocrats but in carrying and caring for soldiers wounded on WWI’s Mediterranean fronts.

Britannic returned to the docks where she was modified for a second time. The first-class dining room was converted into an operating theater. Public rooms in the upper floors were transformed into wards for wounded soldiers. The ship was repainted with a green band that ran from bow to stern and red crosses to indicate she was a hospital ship and, therefore, off limits to enemy fire. Even as a hospital ship, she was a spectacular sight. The ship’s surgeon, Dr. John Beaumont, called her “The most wonderful hospital ship that ever sailed the seas.”

White Star placed her under the command of Captain Charlie Bartlett, an accomplished merchant seaman and Royal Naval Reserve officer. Bartlett had commanded big ships, overseen delivery of Titanic, and had been a part of the discussion about modifying Olympic and Britannic after the Titanic tragedy. Britannic made five voyages, spent some time as a floating hospital ship, and was briefly taken out of service in June of 1916 only to be reactivated in August of the same year. Her luck ran out on her sixth voyage.

On November 21, 1916, she was steaming through the Aegean Sea when, at 8:12 a.m., an explosion rocked the ship. “Suddenly, there was a dull and deafening roar,” remembered Nurse Violet Jessop. “Britannic gave a shiver, a long drawn out shudder from stem to stern, shaking the crockery on the tables, breaking things till it subsided as she slowly continued on her way. We all knew she had been struck…”

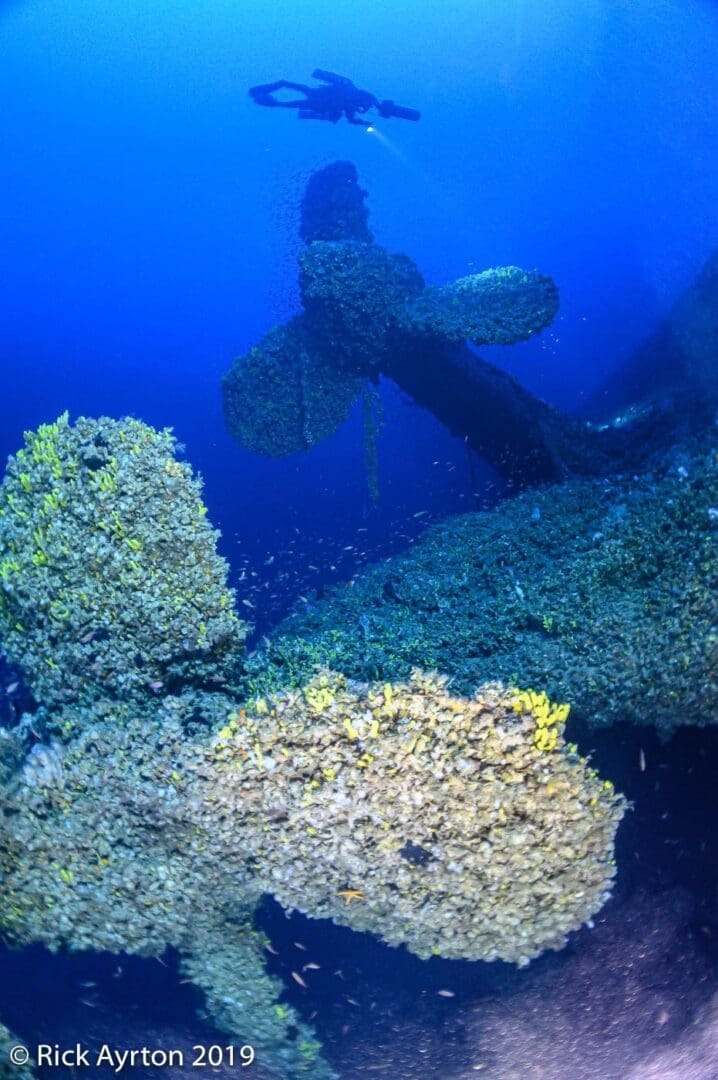

Joe Mazraani swims above Britannic’s massive propellers.

Those on board believed Britannic had been torpedoed by a hidden U- boat, and newspaper headlines in the following weeks criticized the Germans for illegally targeting a hospital ship. Britannic was the victim of a U-boat but not of a torpedo. Records later revealed that U-73, commanded by Captain Gustav Seiss, laid a mine field in the Kea Channel approximately one month prior to Britannic’s sinking. The mines would claim two ships in one week, Britannic and S.S. Burdigala, a French liner also converted for wartime service.

The ship’s bell sounded emergency quarters for everyone on board. The blast flooded six of Britannic’s watertight compartments – damage more substantial than that which crippled Titanic but damage the ship was nonetheless designed to handle. Captain Bartlett was on the bridge at the time of the explosion. They were so close he could see land. He ordered the ship to shore intending to run her aground on Kea Island. He gave no order to evacuate believing that he could outrun the damage.

Britannic’s massive propellers did their best to turn at full speed. What Captain Bartlett did not know was that earlier in the day and against standing orders, the ship’s nurses had opened the portholes to ventilate the ship. Water came pouring through the open portholes as she steamed causing the ship to fill with water and list faster than anticipated. Another thing Captain Bartlett did not yet know was that some crew members had prematurely launched three lifeboats using an automatic release mechanism. They floated in the water near the ship. The list caused rotating propellers to rise high out of the water, and the suction they created drew the lifeboats in. Violet Jessop was in lifeboat number 3. She watched as her shipmates and their boats were shredded by Britannic’s enormous propellers.

“‘Though hands were lowering the boats mechanically, eyes were looking with unexpected horror at the debris and red streaks all over the water. The falls of the lowered lifeboats, left hanging, could now be seen with human beings clinging to them, like flies on flypaper, holding on for dear life, with a growing fear of the certain death that awaited them if they let go.’ Despite the warning of what lay ahead, Jessop’s boat too, was lowered into the water. Jessop had not been paying attention when ‘every man jack in the group of surrounding boats took a flying leap into the sea…They came thudding from behind and all around me, taking to the water like a vast army of rats…I turned around to see the reason for this exodus and, to my horror, saw Britannic’s huge propellers churning and mincing up everything near them – men, boats, and everything were just one ghastly whirl.’”

Captain Bartlett stopped the ship’s engines before the third boat succumbed but not before Jessop and her boatmates threw themselves into the water. Jessop sustained a head injury but survived. Many of those with her drowned. The captain eventually gave the order to abandon ship, and more than 1,000 people boarded the lifeboats from which they were soon rescued. Thirty perished, most of whom prematurely boarded the lifeboats.

Elizabeth Ann Dowse, Britannic’s matron, was with the group who heeded the captain’s orders. She told the newspapers, “Without alarm we went on deck and awaited the launching of the boats. The whole staff behaved most splendidly, waiting calmly lined up on deck…The Germans, however, could not have chosen a better time for giving us an opportunity to save those aboard, for we had all risen. We were near land, and the sea was perfectly smooth.”

Captain Bartlett was the last to leave the ship. He sounded one prolonged blast of her whistle and stepped off the starboard bridge wing into the water before pulling himself into a collapsible lifeboat. The ship’s reverend described Britannic’s final moments:

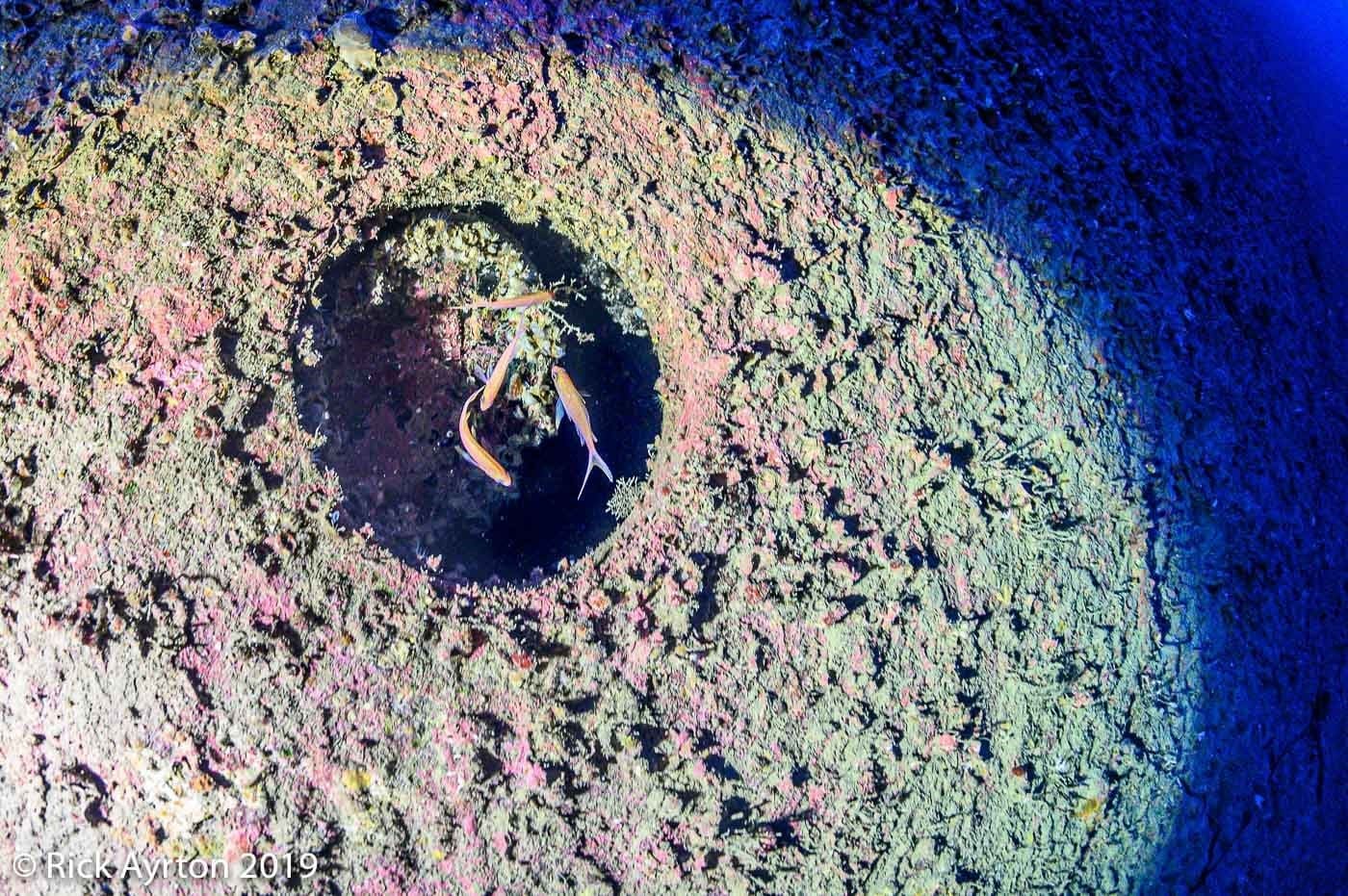

Britannic’s open portholes are now home to marine life.

“Gradually the waters licked up and up the decks – the furnaces belching forth volumes of smoke, as if the great engines were in their last death agony; one by one the monster funnels melted away as wax before a flame, and crashed upon the decks, till the waters rushed down; then report after report rang over the sea, telling of the explosions of the boilers.” When the ship at last sank and there remained nothing but flat calm waters, he felt “a sense of the desert overwhelmed [his] soul.”

The damage sent the 50,000-ton Britannic to the bottom of the Aegean Sea. She currently lays on her starboard side in 116 meters (383 feet) of water. Many of her portholes are still open. Her colossal propellers are still intact. A crack from the mine exposes her bow section just forward of the bridge. She lies waiting for those who are both brave and curious enough to explore her.

There was a controlled chaos at Kea Divers Dive Shop as each diver unloaded case after case of equipment. Everyone on the expedition dove a rebreather of some kind. One by one the divers sighed with relief to find that their equipment made it one piece. A sea of dry suits, bottles, scooters, and the all of accoutrements that go with them came out of vans and boxes and all manner of luggage. Each diver claimed a space and prepared his gear. “Fettling,” is what the Brits called it, a word they defined as the necessary processes of checking and preparing dive gear.

Later in the day, the divers checked their buoyancy in a local bay. The high salinity of the Mediterranean was unlike the more familiar Atlantic and required adjustments. The divers returned to the shop and spread out their gear all over again. This, the Brits called “faffing.” Not to be confused with fettling, faffing is the wholly unnecessary tinkering of gear that goes on long after a diver knows it is good to go. Finally, someone yelled, “Stop faffing!” This was to become the familiar cue to leave the gear behind and enjoy a dinner of fresh fish, Greek salad, and decadent cheeses at one of Kea’s many waterside restaurants.

The team met back at Kea Divers. They sat around a rectangular table outside the shop and discussed the details of the following day’s dive. The group’s first dive was not to Britannic but to S.S. Burdigala, a liner built by the German shipbuilder Schichau Werke for Norddeutscher Lloyd to be both fast and beautiful. In 1912, she was purchased by Cie De Nav Sud-Atlantique, a French Line, and sailed under the French flag from a port in Bordeaux. Burdigala sank on November 14, 1916, just one week prior to the sinking of Britannic – a victim of the same minefield. This shipwreck was discovered more recently and not identified until 2008. George Vandoros and his friend Dimitris Galon were among the divers who identified her in 2008. A stunning sight, she sits upright on her keel at a depth of approximately 260 feet. She provided the perfect way for the team to check their equipment, work through boat procedures, and learn to dive with one another. The team made two dives to Burdigala during their stay in Greece.

Divers Rick Simon, Joe Mazraani, Scott Wyatt and surface support team member Stelios Berketis (left to right) inspect a portion of the bottles before they are transported from Kea Divers to the dive boat.

The mood was quite different the evening before the divers made their first visit to Britannic. Excitement was tempered by a laser-like focus on the task at hand. Britannic was among the deepest dives those in the group had done. For Joe and Rick, it would be the deepest of their careers. There was no room for error.

George Vandoros reviewed the dive and gas plans with the team. Under Scott Roberts’ leadership, the group had discussed, planned, and fine-tuned their mixes long before anyone traveled to Greece. The team dove the same mixes to ease planning and ensure that, in the event of an emergency, every diver and the surface support crew would know what someone needed. The gas mixes were: Tx6/72 (CCR diluent); Tx11/70 (1.4bar @ 117m/383ft.); Tx20/50 (1.4bar @ 60m/197ft.); Tx30/45 (1.4bar @ 36m/118ft.); Tx50/20 (1.4bar @ 18m/59 ft.); and EAN80 (1.4bar @ 6m/19ft.).

Scott Roberts organized the team and set the order of the divers. Yannis Tzavelakos, owner of Kea Divers, gave instructions about the function that he and surface support team members Zenovia Erga and Dimitris Adamis would play clipping bottles to divers, retrieving bottles on the hang, and checking on divers in the water. The team was also briefed by archeologist Themis Troupakis and ROV operator Markos Garras, who joined the team on every dive and monitored the expedition for Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities. Scott Roberts and dive partner Rick Ayrton would be the first in the water.

They, of course, would not be the first divers to lay eyes on the sunken hulk that is Britannic. Albert Falco, Jacques Cousteau’s dive team leader, enjoyed that distinction. Cousteau needed to formally identify the wreck he and engineer Doc Edgerton believed to be Britannic when, in 1975, they first ran over it with a side-scan sonar Edgerton developed. On July 10, 1976, Falco and a few other divers set out to make the identification. They dived using only compressed air. The team expected to be able to see the wreck at 200 feet, so the plan was to descend to that depth, take as many pictures and possible, and ascend to minimize bottom time.

Things did not go as planned. Camera bulbs almost immediately imploded on the descent. When the wreck was not visible at 230 feet, Falco signaled his fellow divers to wait as he descended and buzzed passed the promenade deck to identify the ship. He suffered severely from nitrogen narcosis and signaled to the others that he was in trouble but eventually ascended enough to safely return and confirm the ship was in fact Britannic.

The Calypso returned in September of 1976. This time, they brought with them helium and a diving bell for decompression. Open circuit use of Trimix was only in its early stages, but the circumstances certainly called for experimentation. The gas mixture used by the Cousteau team was Trimix 14/54.14 The team made 68 dives to the wreck.

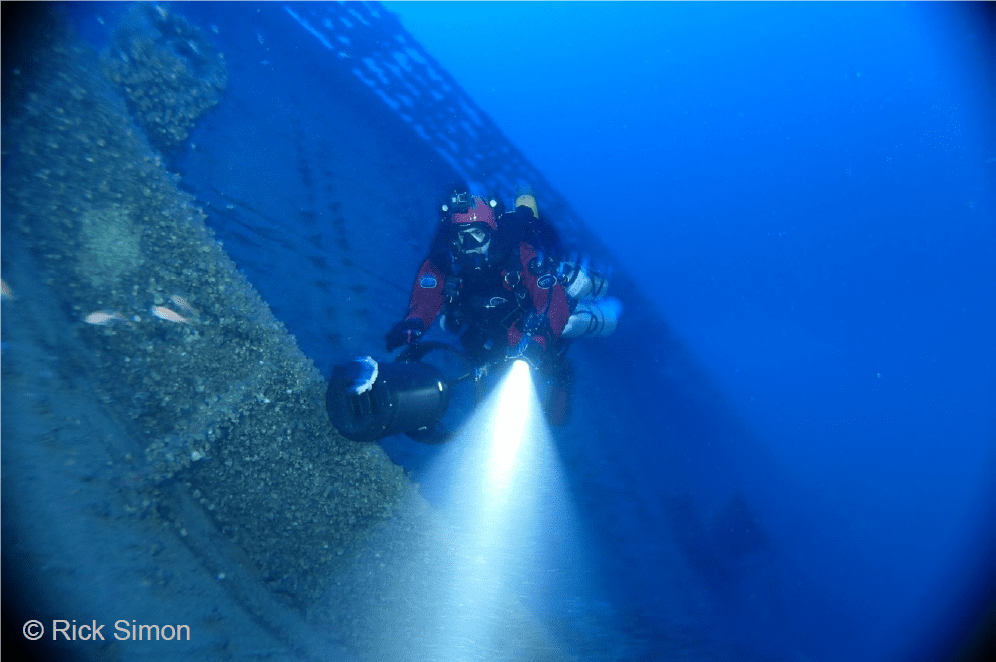

Joe Mazraani swims alongside Britannic’s bow.

Bottom time for each dive was 15 minutes, 9 minutes for descent and 6 minutes at the wreck. Cousteau, who was 67- years old at the time, achieved a depth of 370 feet. Forty-three years later, on May 13, the 2019 Expedition Team got their chance to see what Falco, Cousteau, and the divers of the Calypso saw.

“As you descend, the water turns from pale turquoise to sapphire to an even deeper blue until out of the blueness you see her. All shipwreck divers imagine in their mind’s eye what a wreck will look like up close and in person, but nothing prepared me for my first glimpse of one of the world’s great ocean liners – Britannic. She is massive, mysterious, and perhaps most importantly, full of limitless opportunities for exploration and discovery,” said Joe of his first descent.

The first thing all the divers noticed was Britannic’s size. She is the largest liner on the ocean floor and her scale is like no other. When Joe landed on the hull, he felt as though he was already at the bottom. He looked to the left and to the right. Everything was flat. The ship was so big that he could not see the curvature of the hull. The experience was a bit surreal. It was not until a later dive, when he dropped over the keel, that he finally saw the ship’s curved lines.

Scott Roberts was the first diver from the May 2019 Expedition to see Britannic. No stranger to depth, Scott has an accomplished record of big dives around the world including U-681, the American troopship S.S Leopoldville, the Arne Kjode and a few virgin shipwrecks deemed too deep by prior expeditions. He is a meticulous planner – organized, thoughtful, and careful – qualities which make him not only an excellent diver but expedition leader. Even Scott, a man who is typically measured in his responses, could not suppress his sense of childlike wonder at Britannic. He surfaced and removed his goggles and mouthpiece. His blue eyes were as wide as saucers when he exclaimed, “She is massive!”

The group made two dives to the stern, three to the bow, and one to the midsection. The line to the bow was placed just aft of the bridge, which required the divers to scooter forward. All but one of the divers used scooters, equipment that not only helped speed their descents but allowed them to cover more ground on the wreck. It was a few hundred feet from the bridge to the bow, where the enormous capstans and anchor are visible. At the forward most point of the bow is the railing identical to the one made famous in the movie Titanic. Stern dives featured Britannic’s propellers – two, 23.9-foot, three-blade wing propellers and one, 16.6-foot, four-blade center propeller. Still frozen in time, they were a chilling sight to those who remembered their role in the ship’s tragic sinking. The divers scootered from the propellers up to the fantail. Looking up towards the port gunwale, they saw enormous schools of small fish. As they slowly ascended, empty davits emerged, reminders of the lives saved by the availability and orderly boarding of lifeboats.

Surface Support Team Leader, George Vandoros, checks in on the divers as they decompress on the line.

The divers each did one dive per day. Bottom times ran anywhere from 25 to 35 minutes and involved two- and-a-half to four hours of decompression. While the divers enjoyed the sights below, the surface crew monitored their progress, kept track of depths, and expected surface times, and retrieved excess bottles to lighten the load on the hang. Because all ten divers splashed within minutes of one another and essentially surfaced together, they finished their hang on a trapeze that sat at approximately 20 feet. They passed the hours scribbling wet notes, playing hang man, and drinking packets of energy drinks that the crew left for them.

Conditions on the first dive were pristine. “Don’t get used to this weather,” Yannis warned the group. Miraculously, the seas remained almost as calm for the rest of the trip. It was as if they were the same as those described Britannic’s matron on the day the ship sank. The team made every dive day and totaled 59 dives as an expedition. They were nine dives short of Cousteau expedition but averaged more bottom time at greater average depths on the wreck. Both Cousteau’s and Roberts’ teams retrieved photographs and videos of Britannic that have enabled historians, other wreck divers, and fans of the ship to see what she looks like on the sea floor. Cousteau, however, brought back more than pictures. He brought back artifacts.

Dive after dive in 1976 his crew brought up pieces of the wreck including a sextant with the ship’s name engraved on it, the base of a telegraph, the brass portion of the ship’s wheel, a spittoon, and a small foghorn. The current whereabouts of these items is unknown.

Every member of the May 2019 Britannic team was mindful of the expeditions that came before them. They came to marvel at a legendary wreck, to connect with her history, and to join the ranks those who have reached her. But Joe Mazraani and Rick Simon were on a mission to solve a mystery – one born in 1976 and very much connected to Cousteau’s first dives there.

Rick and Joe, wreck divers who cut their teeth in the waters of the North Atlantic, are no strangers to hunting treasure. They spend most of their summers aboard Joe’s Dive Vessel Tenacious locating, diving and salvaging shipwrecks, which is necessary in North Atlantic waters where the currents threaten to bury and destroy artifacts on the ocean bottom. It was only natural that their Britannic mystery involved artifacts. Whispers about artifacts taken from Britannic by Cousteau have echoed across generations of divers with much speculation surrounding the ship’s bell.

The bell is the heart of a ship. It signals the watch, rings for ceremonies and, of course, sounds the alarm. Bells are among the highest prizes for shipwreck hunters not only because of their sentimental significance, but because they are the easiest way to identify a ship. Made of brass or bronze, bells stand the test of time and are traditionally engraved or embossed with the name of a vessel and the year she launched. The bell of a ship that was not only the largest of its day, but Titanic’s twin sister would have been a crown jewel for an explorer like Cousteau. Some said Cousteau raised the bell and kept it in his private collection. Others said he took it to a museum in Athens or elsewhere in the world. Cousteau, who died in 1997, was silent on the subject. Joe and Rick often wondered if the rumors were true.

The May 2019 Expedition team had the honor of being joined for a portion of the expedition by Britannic’s owner, Simon Mills. Mills’ passion for the ship and respect for divers were apparent as he delighted the team with stories about Britannic and of expeditions past. Mills is not just the owner of the ship but serves as an ambassador for her preservation and has written four books about her including his 2019 release, Exploring the Britannic: The Life, Last Voyage and Wreck of Titanic’s Tragic Twin. His spirit of exploration and decision to open the wreck to divers capable of exploring her mysteries made the team’s dives possible. During one of the group’s dinners with Mills, Joe asked him what happened to Britannic’s bell. It turns out that Mills had wondered too. He told the divers, “When I die and go to heaven, the question I want to ask Cousteau is ‘What did you do with Britannic’s bell?’”

Britannic’s owner Simon Mills and surface support team member Jennifer Sellitti discuss the ship’s history while waiting for divers to surface; photo by Dimitris Adamis.

Joe and Rick enjoyed five dives on Britannic in spectacular conditions, but they were still plagued by questions about the bell and whether Cousteau had removed and hidden it away. They decided to spend their sixth and final dive trying to find out.

They knew where the bell should be. It sat right above the crow’s nest, halfway up the main mast. Britannic’s main mast is broken but still attached to the ship with the topmost part resting in the sand like a massive tree felled in a storm. Joe had buzzed past the area on his second dive but did not stop long enough to thoroughly investigate the area.

The pair dropped into the water and first went to the bow, where they paused to take a photograph Rick wanted to capture. From there, they went straight towards the mast. The divers searched the area of the crow’s nest, but the bell was nowhere to be found.

Rick ascended to photograph the ship from above. Joe remained at the crow’s nest. He had one more idea. He descended and did his best to draw a line from where the bell should have been to the sand below. He fell slowly towards the ocean floor. At about twenty feet from the bottom, he noticed what appeared to be a mounting bracket. He got closer still, and saw the bracket mounted to a gooseneck-shaped object. A field of soft coral surrounded the bracket, which seemed strange considering the rest of the bottom was nothing but sand. It was as if nature itself had marked the spot. In that moment, Joe, who had found ship’s bells before, knew what lay beneath him. He screamed into his loop with exuberance. The effects of the helium raised the pitch of his voice to almost comical heights and made the sound of the discovery even more joyful. “What was I thinking?” he said when asked about that moment. “To be honest, I was thinking ‘Iceberg ahead!’” the line made famous by Titanic’s lookout as he rang Britannic’s sister ship’s bell just before she collided with history’s most famous chunk of ice. as

The gooseneck of Britannic’s bell as seen by Joe Mazraani on his final dive on Britannic

Joe waved his lights and tried to get the attention of the other divers, but they were too far away. Alone in the deep, he contemplated the significance of this find. On his way back to the shot line, he aligned himself with the port bridge wing and ascended, which gave him a clear view of Britannic’s numerous bridge telegraphs, helm, and her telemotor helm. The telemotor helm stood firmly in place, but the telegraphs and manual helm dangled precariously from their attachments. He thought about how fragile they looked. He fears that if artifacts like the bell, the helms, and the telegraphs are not soon rescued, they will be buried in the sand and permanently obscured by marine life.

The divers announced the bell’s discovery in a film presented at the annual Boston Sea Rovers Clinic in March of 2020. Sea Rovers is the country’s oldest dive club and one to which Cousteau, Edgerton and now Rick Simon and Joe Mazraani belong. For Rick, who began his career as a Sea Rovers intern, the moment was particularly sweet. “It was a dream come true to take the stage and share this discovery with the people who have mentored and inspired me.”

Reaction to the news extended well beyond Boston and came not only from divers but from aficionados of the Olympic-class liners around the world. Britannic, after 104 years, continues to captivate new generations. Jake Billingham, who helps operate the Titanic Connections Facebook page and first became fascinated with the liners after seeing James Cameron’s "Titanic," explained it this way:

“Titanic and Britannic have a way of capturing your imagination in a way that makes it feel like you almost were there walking the decks. It is almost like you build a relationship not only with the ships themselves but also with the people that once sailed on them. Immersing yourself in researching these amazing ships lets you experience the tragic sinkings that these leviathans succumbed to, and my fascination with these ships keeps on growing. Even today, the Britannic wreck is still as beautiful as she once was before she sank. These ships and the people that sailed on them become a part of you. It’s almost like your soul becomes one with the souls of the great ships that were so tragically lost.”

Billingham, like Joe at the time of the discovery, could not help but draw the link to Titanic. “The discovery of Britannic’s bell is a symbolic find as it’s a powerful but painful reminder of the events that led up to her twin sister Titanic’s sad and violent end,” he said. “It also stands as a great archaeological find by an amazing dive team.”

The May 2019 Britannic Expedition Team are thrilled by the reception their discovery has received internationally, but for Joe, the greatest satisfaction is personal. In his final dive on Britannic, he cleared the name of his hero, Jacques Cousteau.

Simon Mills had already departed Greece by the time the team made their final dives, but Scott Roberts spoke with him in the days that followed to tell him another Britannic mystery had been solved. Simon paused upon hearing the news. His response was simple. “I guess when I get to heaven, I owe Jacques Cousteau an apology.”

Britannic May 2019 Expedition Team (left to right): Rick Simon, Themis Troupakis, Luke Kierman, George McClure, Joe Mazraani, Jennifer Sellitti, Duncan McCormick, Yannis Tzavelakos, George Vandoros, Zinovia Ergo, Dimitris Adamis, Markos Garras, Rick Ayrton, Jacob MacKenzie, Steve Pryor, Scott Wyatt, and Scott Roberts.

A brass plaque affixed to Britannic honors explorer Jacques Cousteau

The above was adapted from Jennifer Sellitti’s November 2020 article about the May 2019 Britannic Expedition for Titanic Connections. A copy of the full article with footnotes is available on the D/V Tenacious Facebook page.

Boston Sea Rovers 2020 Film Festival

Diver Rick Simon created a film about the Britannic bell discovery. It debuted at the 2020 Boston Sea Rovers Film Festival. Since then, it has garnered more than one million Facebook views. Click on the link below the photo to watch the film

Rick Simon and Joe Mazraani (third and second from right) presented "Britannic's Lost Bell" at the 2020 Boston Sea Rovers Fim Festival. They are pictured with the show's hosts and fellow presenters. Photo courtesy of Boston Sea Rovers.