RMS Lusitania

The following article was featured in the Spring 2022 issue of Voyage Magazine, the official journal of the Titanic International Society. The Society has graciously allowed us to reprint the article here.

Bound to the Sea: An August 2021 Journey to RMS Lusitania

It was as if he had seen a ghost. That is the only way to describe the look on veteran diver Joe Mazraani’s face when he surfaced from a dive to RMS Lusitania. Joe is not only my partner in life but my partner in expeditions to dive sites in North America and around the world. This intimacy allows me to know what has happened on a dive even before he removes his breathing loop, takes his first gulp of fresh air, and speaks. Lusitania was a singular exception. I had never seen that look. It was at once a look of awe, of accomplishment, and of penetrating sadness.

1,201 human beings died on May 7, 1915, when German U-boat, U-20, torpedoed Lusitania. The ship sank within sight of land and in just eighteen minutes. Lusitania was not a military vessel. She was a passenger liner full of men, women, and children. Those aboard included the elderly and infants. They were Americans and Europeans. They were first-class passengers and stowaways. Some died in lifeboats and in the days following the sinking, but most met their end where Lusitania cracked and fell. Disaster bound them all to the sea.

More than 100 years later, the ship lies in pieces, the once-luxurious liner scattered across the ocean floor. The fragments tell a tale of great suffering. A heaviness lingers both above and below the water’s surface at the wreck site as if the sea and the air and Lusitania herself conspire to remind every trespasser of what happened there. The look on Mazraani’s face registered all of it.

A Brief History of RMS Lusitania

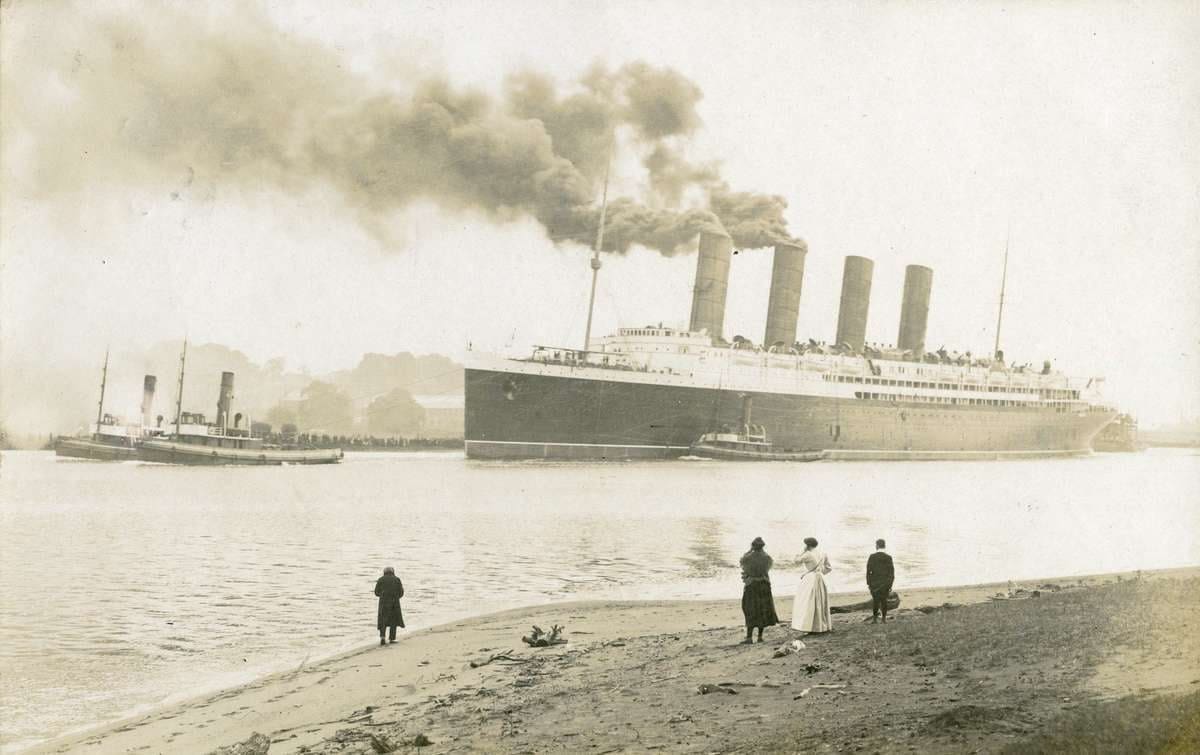

Lusitania, a British passenger ship owned by the Cunard line, left New York on May 1, 1915, carrying 1,962 passengers and crew bound for Liverpool. New Yorkers gathered to bear witness as she sounded the all-aboard and set to sea. She was a spectacular sight. Cunard Line built the ship for the transatlantic passenger trade and launched the liner in 1906. She quickly became synonymous with speed and luxury. The former won her the Blue Riband for fastest transatlantic passage in 1907. Lavish interiors, hotel-style service, and electric lighting and heating won her a reputation for the latter.

WWI raged in Europe on the day Lusitania left port. America had not yet declared war, but there was growing concern about German U-boat activity in the British Isles. Notices in the newspapers warned American travelers they may be subject to U-boat attack, but few believed it, an ignorance Cunard was happy to encourage in wary passengers. Survivors later recalled being told to put the danger out of their minds. The crew told them, “Nothing can harm the Lusitania.”1

Lusitania never arrived in Liverpool. On May 7, 1915, U-20 sent a single torpedo into the ship’s starboard side and sank her to the depths. Of the 1,962 passengers on board, 1,201 perished.2 Ninety-four children and thirty-one infants died. The extraordinary death toll made it one of the worst maritime disasters in history.

German audacity made matters worse. The German Navy bragged about sending innocent civilians to their deaths and created propaganda that glorified the sinking as a military success. The United States would not enter WWI for eighteen more months, but Lusitania was a call to action for many Americans as pressure to declare war mounted. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the British Admiralty, said of the Lusitania disaster, “The poor babies who perished in the ocean struck a blow at German power more deadly than could have been achieved by the sacrifice of 100,000 men."

Lusitania Diving History

Unlike shipwrecks that are lost and rediscovered again many years later, Lusitania did not remain hidden for long. She was rediscovered on October 6, 1935, by the salvage steamer Orphir. The wreck lies at 300 feet/91 meters, which is two-and-a-half times the depth of today’s recreational dive limits. Getting that deep in 1935 was complicated.

Three weeks after the discovery, Orphir lowered diver Jim Jarrett to the wreck wearing a one-atmosphere J.S. Peress Tritonia suit designed by Joseph Salim Peress. The suit looked more like a space capsule than a piece of diving equipment. It weighed half a ton. The heavy metal walls allowed Jarrett’s body to withstand the pressure at depth long enough for him to positively identify the wreck.

Less than a decade later, during WWII, the British Navy regularly depth-charged Lusitania. The official story was that it was to prevent German U-boats from hiding in the shadow of the wreckage, although some say it was to destroy evidence that Lusitania carried munitions.

American Navy diver John Light rediscovered the wreck in the 1960s. He conducted more than forty dives to Lusitania using basic SCUBA equipment and breathing only compressed air. Temperatures in the Irish Sea during the summer months run approximately 50F/10C degrees at the bottom. Immersion in water accelerates the loss of body heat, which is why today’s divers wear dry suits and even heating systems to keep warm during decompression. Light dived the wreck wearing only a neoprene suit. Attempts to photograph Lusitania failed when lights crushed like tin cans under pressure. Lights lowered from the surface allowed Light and his team to take some pictures, but the dangling ropes and cables posed hazards to the divers. Light managed to get some poor-quality photos, but the wreck remained largely undocumented.3

American businessman Gregg Bemis acquired the rights to Lusitania in 1982. Shortly thereafter, Oceaneering surveyed Lusitania and salvaged the vessel. Oceaneering teams descended upon the wreck in 1982 and 1983. Divers decompressed in a two-man dive bell with a saturation chamber attached to the support ship. Their suits were equipped with hot water circulation systems to combat the cold. The corporation cut away anchors, propellers, and other items during this massive and destructive private salvage effort.4 Some of these artifacts are on display in various parts of the world while others have gone missing.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, with Robert Ballard, surveyed Lusitania in May 1993. The result was a National Geographic film and magazine spread documenting the wreck and her condition. Exploring the Lusitania: Probing the Mysteries of the Sinking that Changed History introduced a new generation of divers to the ship and her unique place in history.

It was around this time that the advent of closed-circuit rebreathers (CCR) and the widespread use of mixed gases started allowing ordinary people to reach extraordinary dive limits. Acceptance of these two technologies in the 1990s ushered in the age of modern expeditions to shipwrecks like Lusitania and Britannic. Mixing helium with oxygen and nitrogen allowed divers to avoid oxygen narcosis, a type of disorientation that can affect divers at depth, and to better combat decompression sickness. Rebreathers, equipment designed to recycle the gas divers breathed, meant they were no longer limited by how much gas was in their tanks. Bottom time changed from a function of how much gas a diver could carry to how much decompression they were willing to endure. Today, expeditions to Lusitania are comprised almost exclusively of CCR divers.

The August 2021 Expedition

The August 2021 Expedition Team consisted of eight CCR divers, four American and four European: Rick Ayrton, Andrew Donn, Jacob MacKenzie, Joe Mazraani, Steve Pryor, Scott Roberts, Rick Simon, Joe St. Amand. With the exception of Donn and St. Amand, the team had dived together previously as part of an expedition to Britannic in May of 2019. Roberts led the Britannic expedition, which made news around the world for the discovery of the ship’s bell. Lusitania was a natural follow up.

Mazraani and Roberts, by now not only dive teammates but close friends, co-led the expedition to Ireland. “It was important and fitting that our expedition was put together from both sides of the pond,” noted Diver Steve Pryor, “There is an incredibly sad story behind Lusitania that features the history of us all.”

The team lived and worked out of Kinsale, a small Irish town on Ireland’s southern coast hallmarked by brightly colored row houses, local pubs, and a thriving tourist scene. Our base of operations was South West Technical Diving, a dive shop owned and operated by Matt Jevon. Jevon’s shop is unique in that it is located not on the water but inside an enormous barn on a working cattle farm. Upon arrival in Ireland and each evening after dives, Jevon and the team labored with equipment and filled tanks accompanied by the sounds of mooing cows and the calls of farmhands. “It’s a beautiful place to work,” said Mazraani. “Matt welcomed us to the shop and gave us free reign of the place for as long as we needed. We are grateful to him for his hospitality.”

Most journeys to the Lusitania dive site leave from picturesque Kinsale Harbor. Ours was no exception. Although other operations will take divers to Lusitania, most use Captain Gavin Tivy’s boat, Sea Hunter. Tivy is Hemingwayesque with warm eyes, a bushy beard, and a smile that at once reveals his friendliness and his intellect. There is a reason most serious expeditions choose Sea Hunter. Tivy is a diver and an experienced captain. Sea Hunter has been instrumental in assisting the Irish government, under strict permits and archeological protocols, with the retrieval of artifacts from Lusitania and other historic vessels in the area. He knows these waters and the ships that rest there like the back of his hand.

Tides at the dive site control when Sea Hunter leaves Kinsale Harbor, but most were early morning starts. The journey was a noisy one filled with the chugging of the boat’s engine, the clinking and clanking of dive gear, and the chatter of divers discussing their plans for the day.

The sounds changed when, after a two-hour steam, the boat reached the site of Lusitania’s demise. The engine idled. The divers focused. The mood changed from one of excitement to one of intensity. Divers methodically prepared to drop into the water, a practice hastened by years of experience. For the surface support crew members, the tasks moved from making last-minute notes about dive plans and gear configurations to getting divers into the water as safely and efficiently as possible. They dropped on the wreck one by one, in pre-determined order, with the goal of getting to Lusitania and back in as much of a group as possible. One after another, they stepped to the platform, awaited the signal, and splashed. They hovered on the surface, their brightly colored gear momentarily disrupting the blue, until they slipped beneath the waves and disappeared.

“As one descends the line, the ambient light fails quickly and the darkness below envelops you,” said Pryor. Divers cannot see the wreck from anywhere near the surface. They follow a rope line, called a shot line, for 300 feet (91 meters). What is it like? “It gets darker and darker and darker until you reach the bottom,” Mazraani described it the only way he could, “There, it is dark.” Diver/photographer Rick Ayrton passed the descent by performing final checks and procedures. “Time passes in a whirl as you descend,” he said. “Light fades to inky darkness and then, there she is.”

Unlike shipwrecks that rise-up in identifiable chunks from the ocean floor, Lusitania is, as Mazraani describes, “parts and pieces.” There is wreckage scattered everywhere, the product not only of U-20’s torpedo, but British Navy depth charges and the 1980s salvage. Natural conditions have further contributed to the wreck’s deterioration. Unlike Britannic, which is relatively intact because of its location in far less-volatile waters, Lusitania has been battered by the North Atlantic’s notorious currents, tides, and constantly shifting sands. The darkness and the rubble made landing on Lusitania both eerie and disorienting.

“As you land finally on the wreck, you are thrown straight into an initial maelstrom of activity as all divers orientate themselves before setting off in exploration,” Pryor added. “There is no view of what is recognizably a whole ship, but rather a debris field.” Ayrton said, “You fumble to attach a strobe light, check the camera is working as it should, tie on the distance line, and away we go.”

Diving the Forward Section

The team made six dives to the wreck: two in the forward section, three amidship, and one in the stern. Diver Andrew Donn was immediately struck by the ship’s “sheer size and opulent fittings.” Pryor was “amazed at the scale of the wreck.”

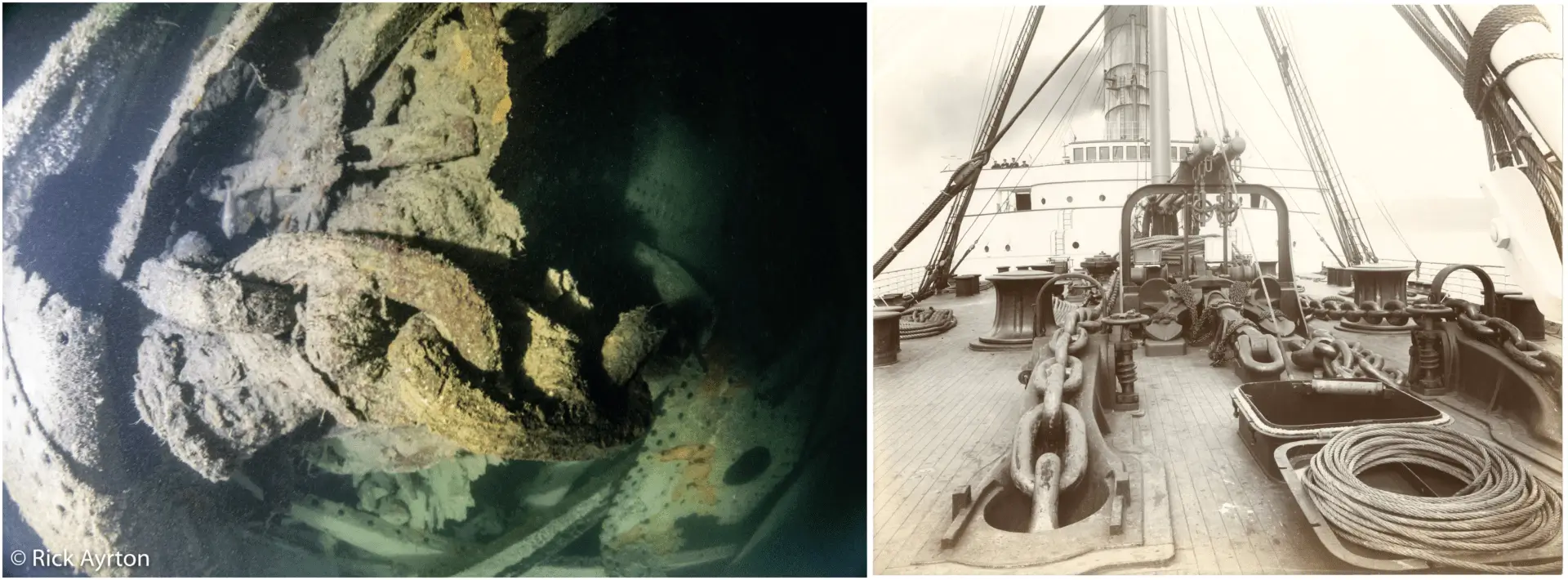

Lusitania’s forward section features remnants of the bridge, the area from which Captain Tuner and his crew operated the liner on its final voyage. Here, large items used by the captain and his men are frozen in time. The telemotor helm, part of the hydraulic system used to the steer the ship, is visible. It was used to transmit commands to the steering engine and turn the ship’s rudder. Smaller and more delicate items hide beneath the wreckage, including what appears to be an intact bridge compass, which the crew would have used in navigation.

One of the most magnificent sights in this area is Lusitania’s triple chime steam whistle. One of the three chimes is covered with sand, but the remaining two are visible. The whistle is of substantial size, and the girth on the chimes is massive. On our visit, the chimes were closely guarded by an octopus and one of the pipes had found a new purpose as home to a large crab.

It is the whistle’s significance, however, that makes it such an important artifact. Whistles are often referred to as the voice of a ship. Lusitania’s chimes each bore distinctive notes and gave her a voice with high notes and bass, with dimension and beauty. Shipboard whistles sound in all manner of circumstances are used to signal in times of joy and in times of danger. It was Lusitania’s whistle that signaled farewell when she left New York. It was her whistle that rang in the ears of onlookers as their loved ones slipped to sea. “It is chilling to think that every passenger and every member of the crew heard that whistle as the liner left port for the last time,” remarked Diver Joe St. Amand.

The crew’s domain is marked by enormous capstans, bits, bollards, and chain boxes. The men used the capstans to help haul ropes, chains, and anchors onto the ship’s deck and into her holds. Bits and bollards secured mooring lines, ropes, hawsers, and cables.

Wreck divers are a rare breed. They become so focused on the dive that they ignore, or at least momentarily compartmentalize, the experiences of those who lived and died a ship. Ayrton rarely thinks about the victims of a shipwreck during the dive. This is not out of callousness but out of necessity in what is a dangerous environment. “I spend too much time monitoring my dive, checking my life support systems, and trying to take decent photographs.”

Not so with Lusitania. The darkness and the metal carnage made it difficult for even the most focused diver to forget what befell her on the afternoon of May 7, 1915. Donn explained:

“On a dive of this magnitude, one can’t help but think about the passengers and crew during the dive. We did not encounter personal artifacts, but you are reminded of the people through the parts of the wreck that they would have interacted with; doorways they would have walked through, windows they would have looked out of. As you look down the row of bridge windows, it is easy to imagine the captain and his crew looking out as they steered the Lusitania close to the Irish coast. It is easy to be impressed and almost overwhelmed by the wreck itself, but there are constant reminders of the people that make up the real story of the Lusitania.”

Even Ayrton fell victim to Lusitania’s ghosts, “I saw a rope coiled around the ship’s bollards. It intrigued me to know the name of the seaman who last coiled the rope.” He wondered, “Did he survive? What was his story?”

Irish law prohibits any diver from removing or interfering with items on the wreck, but there is a notable exception. In May of 2015, one hundred years to the day of Lusitania’s sinking, Irish Diver Eoin McGarry left on the wreck a special memorial, a metal scroll that contains the names of all 1,201 victims. He personally secured the scroll to one of Lusitania’s prominent features, a large skylight.

McGarry has dived Lusitania more than any man alive. He grew up on the sea, in Ireland’s Ardmore region, about two hours east of Kinsale. Some his first dives were to Folia, another Cunard liner resting in shallower waters near McGarry’s childhood home. He first met Bemis many years ago when he wrote to him to seek permission to dive Lusitania. He was not expecting a response, but he received one. Never in his wildest dreams could he have imaged what would follow: a relationship that began in that moment and endures until today, even after Bemis’ death.

McGarry joined us on two of our dives to Lusitania. He has a welcoming personality but, beneath the surface, resides a quiet contemplation. He is engaging, smart, and knows more about diving Lusitania than anyone. He is also extremely cautious. He sizes up anyone who plans the dive the wreck like a man who just found out you are dating his daughter.

He has good reason. Bemis willed ownership of Lusitania to the Old Head Signal Tower Committee and Lusitania Museum when he died. The decision to donate the wreck to the museum was made after careful deliberation and concern for Lusitania’s future. Although the Committee is the wreck’s legal owner, the Irish government dictates who gets permits to do everything from dive the wreck to recover artifacts. Much to McGarry’s dismay, permission to raise artifacts has halted in recent years. McGarry serves on the Signal Tower Committee and acts as a liaison between it and the Irish government. It is a careful dance that requires him to make sure divers know the boundaries and respect the privilege that is diving one of the world’s most important shipwrecks.

It is also personal. Bemis died in 2020. Before his death, he bestowed upon four men the title of “Lusitania Steward.” Bemis created four, identical bronze badges with an etching of the wreck, the word “steward” written across the top, and an anchor over the words “Cunard Line” across the bottom. The badges were made to look like worn and aged coins. Bemis kept one for himself and awarded the remaining three to his son David, Con Hayes of the Old Head Signal Tower & Lusitania Museum, and McGarry. Steward is not a title that comes with any legal significance, but it is a title more important to McGarry than any other. It was the word chosen by his friend and “father-figure.”5

It is one that signifies their mutual respect and shared commitment preserving Lusitania’s history, memory, and story. To be a steward, means to look after, to care for, to be responsible. It is a designation that forever binds McGarry to Lusitania and her to him.

McGarry remembers the day he left the scroll on the wreck. He planned to dive just after 2:00 p.m. on May 7, 2015, 100 years to the minute of U-20’s torpedo strike. “The weather had been terrible. It blew hard for a week,” McGarry said.6 Miraculously, the weather turned, and seven minutes past two turned slack tide, the best time to dive the wreck. “I dived Lusitania exactly 100 years to the minute to the hour of the sinking.”

He dived alone. His dive was short, but even short dives on Lusitania require penance in the form of decompression. Many divers find the decompression process meditative. There is not much to do to bide the time; and, in dark water, there is not much to see. Divers are left alone with their thoughts for hours. It was that way for McGarry on May 7, 2015, as he hung suspended somewhere between Lusitania and the surface.

It was then he had what he referred to as “a transition.” “I looked up, and I could see peoples’ legs in the water.”7 He suddenly saw what it looked like all those years ago. He envisioned the people in the water struggling for their lives. “You can picture the captain, you can imagine the torpedo, you can see the chaos and hear the screaming, and then you look up to the surface where it’s all calm, and you can imagine the plume of bodies falling around you.”8 In that moment, he transitioned from a tourist diver and working diver to something else. “The whole wreck became personalized,” is how he described it. “That, by far, was the most moving dive I’ve had.”9

Diving Amidship

The damage to the vessel is evident amidship, just behind the bridge, where the torpedo struck. Here, in addition to a large debris field, there are some more structurally substantial areas, places where divers can go inside the wreck and explore. The boilers are located amidship. They have been the focus of debates about whether a ruptured boiler caused a secondary explosion that hastened Lusitania’s sinking. Getting to the boiler area required divers to duck underneath wreckage and penetrate an interior compartment. There, two massive cylindrical objects confronted them. Lusitania had 23 double-ended and two single-ended boilers situated in four boiler-rooms. Only a small portion of those boilers are visible. The rest are buried too deep within the ship to make it possible to know how many are still intact and if any exploded.

Amidst the amidship wreckage, however, divers found glimpses of what Lusitania once was. There were smaller artifacts here, things that people who once traveled on the great ocean liner used and touched. Ornate windows, portholes, and chamber pots are caught in piles of sprawling debris. Rick Simon, who most frequently dives in the waters off New York, where recovering artifacts like portholes from sunken vessels is legal, laughed, “I saw so many intact portholes that I had to stop myself from taking more pictures of them!” There is China hidden in the wreckage, some broken and others whole. All of them bear the distinct Cunard logo, a lion holding the world between his two paws.

Dives to this area brought home for the team the importance of artifact preservation and recovery. Shipwrecks are not static. They crumble and collapse upon themselves in time. The glass on many of the windows and portholes has already been smashed. The compass and chamber pot are in immediate danger of being crushed by falling wreckage. The North Atlantic’s notoriously harsh conditions create an inhospitable environment for shipwrecks. Tides, currents, storms and shifting sands all take their toll; and they all contribute to Lusitania’s deterioration. As Donn put it, “Everything that is left on the bottom will eventually be reclaimed by the Atlantic and lost to history forever.”

Fishing vessels pose additional threats to the wreck. The Irish government has restricted removal from objects from Lusitania, but they have not restricted access to the area by fishermen. Nets and monofilament cover Lusitania, including an enormous collection of nets in the stern. McGarry described it succinctly, “[T]he nets are strangling the wreck.”10

Fishing nets are strong and could easily drag a large artifact away. It has happened before. In 1965, a net from the fishing boat Croidte an Dúin ripped a steel lifeboat davit from the wreck site. The davit was placed in a park in Kilkeel, an Irish town with no connection to Lusitania. She remained there unmarked for more than three decades. It took more than forty years for the davit to be transferred back to Kinsale.11 It now graces the Lusitania Memorial Garden and points in the direction of the disaster site. Large items like a telemotor helm and the steam whistle could be ripped from the wreck next if not rescued and restored.

Hayes, McGarry and an incredible team of people at the Old Head Signal Tower & Lusitania Museum are hoping to preserve Lusitania artifacts for future generations. Hayes, who is one of Bemis’ Lusitania stewards, is a tall Irish gentleman with bright blue eyes, wispy white hair, and the warmest of hearts. He serves as Committee spokesperson and as one of Lusitania’s fiercest advocates. Hayes is not a diver. The closest he has come to Lusitania is a topside visit to the wreck site. He understands all too well that sharing artifacts with members of the public who cannot possibly reach Lusitania’s depths is the only way to keep her memory alive.

The museum will be located at the Old Head of Kinsale. There already exists on this site a 18th century signal tower, a small museum with a few Lusitania artifacts, and the Lusitania Memorial Garden. A dedicated museum space for Lusitania artifacts and exhibits is the next phase in the site’s evolution. Hayes and his team have commissioned architectural drawings and have begun to raise money to turn the dream into reality. It is the Committee’s hope that building the new museum will convince the Irish government to issue the permits necessary to resume raising and restoring artifacts before it is too late.

One extraordinary feature of the Lusitania Memorial Garden is a sculpture called “The Wave.” The 65-foot/20-meter-long memorial, created by Cork artists Liam Lavery and Eithne Ring, tells Lusitania’s story in a series of metal panels. The panels move chronologically, beginning with the ship’s launch and ending with funerals held for the dead at the Old Church Cemetery in Cobh. The Wave also lists the name and fate of every person who traveled aboard the ship on her fatal voyage.

Standing the Wave’s presence is overwhelming. The list of names etched in a bronze, ribbon-like pattern seems endless – a string of souls collected by Lusitania and bound to the deep. “The Wave is one of Ireland’s wonders,” said McGarry of the sculpture. “It needs to be seen to be believed.”

The same can be said of Lusitania. The problem is that only handfuls of people get to see the once magnificent ocean liner. Divers with the technical skill to reach depths of 300 feet/91 meters are the fortunate few who can admire her steam whistle, look through her windows, examine her telemotor helm, and view her unrecovered telegraphs. Artifact recovery, conducted in cooperation with the Irish government, is the only way the public will ever be able to see and appreciate this shipwreck up close. Donn explained, “Images and written accounts are great, but nothing compares to seeing a piece of history with your own eyes. By recovering artifacts, we would be able to share the history of the Lusitania with many in a tangible way that is now only possible for a select few.”

Names fade with time. So do stories. “Most of the traces of the departed are gone from the wreck,” said Pryor. “It is if they are ascended.” Museums are the temples we visit to connect with our past. Creating a space where Lusitania’s treasures can be observed by all is the way we honor the dead and give the names on the Wave their humanity and their meaning.

Diving the Stern

There’s an Irish saying that goes, “In Ireland, you can experience all four seasons in one day.” When a dive crew crosses the Atlantic to get as many dives as possible in a two-week period, waiting on ideal conditions is an unaffordable luxury. You dive when you can. While the Celtic gods did not frown upon our expedition, they did not exactly smile either; it was more of a smirk. The August 2021 Expedition got six dives on Lusitania, but not one of those dive days could accurately be described as calm. We worked for all of them. One of the days the Irish Sea really kicked us in the teeth was the day the team dived the stern.

Kinsale Harbor is protected by two land masses, the Old Head and the area that is home to 17th century Charles Fort. The wind strengthens, and the seas become rougher as boats pass this point because they are no longer sheltered by the land. On some days, Sea Hunter had to “poke it’s nose out” just beyond the Old Head before we could be certain the weather was good enough to proceed.

Tivy owns Sea Hunter, but he divides captain duties between himself and another man, Captain John Griffin. Griffin was with us for the worst of our weather days, and we were lucky because of it. Griffin grew up on a farm in Ireland’s interior. Tradition dictated that the family business pass to him, the eldest son. Griffin loves the land but prefers the sea. He was glad when his brother decided to take over the farm and freed him to pursue his dream of making a living on the water.

Griffin had a distinguished career as captain and sailing instructor and continues to serve with the Royal National Lifeboat Institute, an all-volunteer crew that provides twenty-four-hour rescue service in the UK and Ireland. His experience shows. He reads the sea, the waves, and the winds to protect passengers and crew from dangerous conditions. He does it all with a childish grin as if every second on the water is full of wonder for him even after all these years.

The surface support team was comprised of the captain, a deckhand, and me. Getting eight divers, all with different gear configurations and last-minute needs, into the water in quick succession can be challenging. The average bottom time, or time at depth in our expedition, on Lusitania was roughly thirty minutes, sometimes a bit more. Once the last diver jumped into the water, those of us on the surface knew we had about thirty minutes to ourselves before we started searching for signs that the divers had begun their two-three-hour decompression. Teatime, we called it.

“Teatime!” Griffin would shout when the last diver stepped into the water. “Coffee? Tea? Biscuit?” Griffin is a natural storyteller. Teatime meant not only a warm drink but a story or two. In a thick Irish brogue punctuated only by the drag of his cigarette or a sip of his beloved Barry’s tea, he passed the thirty minutes spinning yarns about Lusitania expeditions gone by, telling tales of the sea, and pointing out the local wildlife. An outsider might make the mistake of thinking Griffin was wrapped-up his stories, but his eyes were always on the water. The slightest change the wind or surface condition caused him to spring to the helm until he was certain all was well. Drinking from his endless well of knowledge, and from his supply of Barry’s tea, was one of the best things about being on the boat with divers in the water.

The weather on our last dive started out fine enough but changed during Teatime. Griffin called what was by now a familiar refrain, “The wind is freshening, Jenny.” That it was. The wind had switched directions creating chop and swell. There is no communication between divers and support crew on these dives. The team below is oblivious to what is happening on the surface and us to them. We each work in our own realms, trusting the other. On the surface, we passed the final dive preparing for what we expected would be a difficult hang in rough seas.

Meanwhile, the divers did their thing. Our final dive was the team’s first and only dive to Lusitania’s stern. If Lusitania is another world, the stern is another dimension. Explosives and machinery used during the 1980s salvage devastated this section. The result is a jumbled mess of metal fragments strewn across the ocean floor like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. The team poked around the stern. Some swam out into the debris field to explore its fringes. All enjoyed their last thirty minutes with Lusitania.

Last dives seem to be magical for this team. It was on their last dive to Britannic that Mazraani discovered the ship’s long-lost bell; and it was on the last dive to Lusitania that Ayrton contributed to her history. While exploring the stern, Ayrton came across what at first appeared to be a large piece of metal or wood. He realized on further inspection that it was a large piece of glass covered by a thin coating of sand. Beneath the sand, he saw small patches of bluish-white peeking through. He fanned the sand away to reveal larger blue sections. He had no idea what it was, but the baby-blue opaque glass was unlike anything he had seen elsewhere on the wreck. His bottom time was running out. He photographed what he saw and excitedly waived some of the other divers over before he and his dive buddy, Jacob MacKenzie, returned to the shot line to begin their ascent. Soon, the remainder of the team returned to the line and did the same.

No one on the August 2021 expedition fancies themselves a Lusitania scholar. The group assumed someone before had documented this “Blue Panel.” Our research revealed little, so we called upon the ocean liner community to find out. We learned that Ayrton was the first to observe and document this find. It was “without a doubt” the highlight of his trip. “I also feel guilty that my dive buddy Jacob didn’t get to see it because we were running out time and needed to return to the shot line,” he said. Thankfully, his photographs preserved the moment, not just for Jacob MacKenzie and the team, but for Lusitania aficionados around the world.

The mystery remained. What was the Blue Panel? Given the location and input from Lusitania scholars, we now believe that the glass came from the second-class smoking room, located on Promenade deck ‘B’ just aft of the staircase. “The smoking room was decorated with mahogany paneling, blue-tinted sliding windows, white plasterwork ceiling, and a dome.”12 “The smoking room was 52 feet (16 m) with mahogany paneling, white plaster work ceiling and dome.”

McGarry was with Griffin and me on the surface for the last dive. None of us up there waiting for the team of eight divers knew anything about a Blue Panel that had not been seen in more than 100 years. All we knew is that the weather had gone from tolerable to suboptimal. We kept eyes on the divers and assisted them by dropping lines into the water and hauling equipment they no longer needed to the surface. The hang was as difficult as we predicted. The rough water near the surface caused a few of the team to resort to decompressing on emergency equipment, a way to minimize bouncing up and down in lumpy seas. The procedure was not necessarily unusual under the circumstances but required those on deck to be even more vigilant as drivers drift away from one another.

McGarry and I hauled equipment and kept eyes on the divers. The worsening weather sent water splashing over the back of the boat where we worked and drenched us to the bone. Neither of us seemed to mind. Last dive days are kind of like that – exhausting, and yet, extremely satisfying.

One by one the divers broke the surface, and the boat gently swung around to pick them up. They removed their gear and filed into the cabin where hot drinks and sandwiches awaited them. There was a lightness to them. Toasts in commemoration of the expedition soon followed.

I felt my own sense of relief. There is no time for daydreaming or reflection when eight people you love are diving in these conditions and to these depths. It is only when all divers are safely aboard that I even allow myself to think about the dangers and the wonders of being in a place like this. A peace came over me as I saw them laughing, toasting, and beginning to swap stories about the final dive.

As Captain Griffin revved the engine and we started to make our way back to Kinsale, I turned and took one last look at the spot where Lusitania fell. I breathed in the sights and the sounds and the joy in the air. The moment was interrupted by a chill that came so suddenly it pierced the serenity clean through. The sea’s noises amplified. I heard a hiss in the wind. Choppy black waves reached up from the water like fingers from below. I thought about McGarry on his centennial dive and about the visions he saw not just of a ship but of those who lost their lives. I did not see them, but I could feel them. The feeling can best be described as one of taking weight on the soul. It was a silent transfer of obligation to honor this place.

There are many shipwrecks in the world, but few are steeped in a combination of such history and such tragedy. Most go to Lusitania because of the moment in time she represents, but they return for so much more. There is something to learn in every piece of twisted metal, in every dark corner, and beneath every layer of sand, but; perhaps more importantly, there is also something to feel. Lusitania is a siren. She takes and she gives. She haunts and she inspires. She does not give up her secrets easily; and, once she does, she does not let go. The members of the August 2021 Expedition team each traveled to Ireland in search of Lusitania. Little did we know she was also in search of us. We are all bound to her now and forever changed because it.

- Account by survivor Grace McFarquar, https://www.rmslusitania.info/people/second-cabin/grace-macfarquhar/

- Some accounts list the totals as 1,959 on board and 1,198 deaths. This does not include three German stowaway who perished aboard Lusitania. The current owners of Lusitania, the Old Head of Kinsale Signal Tower Committee, include the three stowaways in the totals, and we do as well.

- O’Sullivan, Patrick, Getting to the Bottom of the Lusitania Sinking, Irish Times, October 21, 2014.

- Oceaneering used explosives and cut away large sections of the wreck. It is important to distinguish this type of destructive salvage from the removal and restoration of artifacts in a way that protects the integrity of the wreck. Our team advocates the latter.

- Divernet, Lusitania Owner Bemis Dies at 91, May 23, 2020.

- Tenacious LIVE with Eoin McGarry and Con Hayes, April 18, 2021; available on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4v8Nu3vk7zo&feature=youtu.be

- Tenacious LIVE with Eoin McGarry and Con Hayes, April 18, 2021.

- English, Eoin, Diver Eoin McGarry to Lay Plaque on Wreck, Irish Examiner, May 5, 2015

- Tenacious LIVE with Eoin McGarry and Con Hayes, April 18, 2021.

- English, Eoin, Diver Eoin McGarry to Lay Plaque on Wreck, Irish Examiner, May 5, 2015

- Campbell, Cormac, Lifeboat Davit from Lusitania Wreck Leaves County Down, BBC News, April 5, 2018.

- Peeke, Jones & Walsh-Johnson, The Lusitania Story, pp. 18–20, (2002).

Lusitania's Legacy

Jennifer Sellitti and Rick Simon joined forces to create a eighteen-minute film about the Lusitania disaster for the Boston Sea Rovers 2021 Film Festival. The film, "Lusitania's Legacy," chronicles the ship's sinking both through the eyes of survivors and through the eyes of divers exploring the wreckage on the sea floor. The film highlights the importance of the salvage and restoration of artifacts from Lusitania for future generations to enjoy. It lasts eighteen minutes long - the exact time it took Lusitania to sink. The film is slated to be released to the public in 2024 as part of the Old Head Signal Tower & Lusitania Museum's plans to raised funds in the United States to support the building of the new museum at the Old Head of Kinsale.